Vienna, former capital of the Habsburg Empire, is one of my favorite cities. Last summer I took my family there for two months and directed a BYU study abroad program; five years before that I did the same thing. What an amazing place for a musician! The history of the trombone in the “City of Music” and its surrounding territories is quite colorful and differs in many ways from the trombone’s history in other European centers. Below are some related entries that I am adding to the Trombone History Timeline, Early Literature, and Rear-facing Trombones pages. Enjoy!

1630—Regensburg, Germany: A Mass in connection with the coronation of Eleonora as queen of the Romans is performed by the imperial singers and instrumentalists, including trombones (Saunders, Cross, Sword, and Lyre 199).

c. 1633—Vienna, Austria: Although the printed version of Giovanni Priuli’s 12-voice motet, Pascha nostrum (1619), contains no indication of instrumental participation, the manuscript copy (c. 1633) assigns six of the parts to instruments: three to trombones, one to violin, one to cornetto, and one to either violin or cornetto” (Saunders, Cross, Sword, and Lyre 28).

1660—Vienna, Austria: Johann Sebastian Müller, a Saxon diplomat, sightseer, and diarist, visits Vienna, where he attends the “clothing and introduction ceremony” of an imperial Kammer-Fräulein (lady-in-waiting) at the Königinkloster. As part of the ceremony at the church, “instrumental music was performed with four choirs of instruments: one with violins, theorbos, and violas da gamba; a second with trombones and cornetti; a third with trumpets and timpani; and the fourth with high trumpets” (Page, Convent Music 19).

1729—Vienna, Austria: Georg Reutter’s Mater dolorum, performed at the convent St. Agnes zur Himmelpforte, calls for a trombone. In the surviving parts the trombone’s single obbligato aria is labeled “Trombon: Alto solo. ô Talia,” suggesting an alternate instrument may have been used (Page, Convent Music 221).

1740—Vienna, Austria: By this date, the practice of using trombones to augment forces at the Ursuline convent is well established, with sets of parts that often include a pair of trombones” (Page, Convent Music 84).

1743—Vienna, Austria: On St. Leopold’s day the chronicler at the Ursuline convent records, “There were trumpets and timpani for both Litanies, and also for the Mass, but there only the fanfares. For the first Litany and at Mass there were trombones [posannen]” (Page, Convent Music 218).

1743—Vienna, Austria: On the feast of St. Ursula the chronicler at the Ursuline convent records, “at both Masses we had trombones, but we did not have them for Second Vespers” (Page, Convent Music 219).

1745—Vienna, Austria: A solemn festival of thanksgiving upon completion of the Ursuline convent features a High Mass and Te Deum with trumpets, timpani, and trombones (Posanen). These instruments also play for Vespers (Page, Convent Music 25, 209).

1746—Vienna, Austria: The chronicler for the Ursuline convent reports that, because of a decree that no trumpets or timpani are to be used for liturgical services, “Sister Maria Francisca’s profession ceremony took place…along with our musicians there was nothing else but the trombonists [possaunen]” (Page, Convent Music 209).

1750—Vienna, Austria: At the Ursuline convent, music for the celebration of Mass on the feast of Philip and James includes trombones (pusunnen) (Page, Convent Music 84).

1751—Vienna, Austria: At the Ursuline convent, on the feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the convent chronicler reports, “we had no trumpets this year; at the service we had nothing but trombones.” The same holds true of other important feasts of the year: the abbess’s name day, St. Mathias, and St. Ursula (Page, Convent Music 212).

1751—Vienna, Austria: Trombones are used for a Requiem Mass at the Ursuline convent (Page, Convent Music 220).

1753—Vienna, Austria: Trombones are hired to play at the Ursuline convent with the convent’s musical ensemble on the abbess’s name day (Page, Convent Music 218).

1753—Vienna, Austria: On St. Ursula’s day at the Ursuline convent, the convent chronicler reports, “trumpets and timpani as well as trombones played for the Mass…for First Vespers [on the eve of the feast] as well as [Vespers] on the feast itself, only the trombones [possounen] played” (Page, Convent Music 213).

1754—Vienna, Austria: Trombones are added as extra musicians for a ceremony at the Ursuline convent (Page, Convent Music 27).

1754—Vienna, Austria: Trombones are used for a Requiem Mass at the Ursuline convent (Page, Convent Music 220).

1760—Vienna, Austria: In this year or earlier, Marianna Martines writes her Mass No. 1 (Messe no. 1), where the two trombones double inner choral parts (Godt 35, 37).

1760—Vienna, Austria: Marianna Martines writes her Mass No. 2 (Seconda messa in G) where the two trombones mainly double inner choral parts but are featured on obbligato parts in the Benedictus (Godt 35, 37).

1761—Vienna, Austria: Marianna Martines writes her Mass No. 3 (Terza messa), where the two trombones mainly double inner choral parts but are featured on obbligato parts in the Benedictus, accompanying a tenor solo (Godt 35, 37, 45; Godt Chronology).

1765—Vienna, Austria: Marianna Martines writes her Mass No. 4, where the two trombones double inner choral parts (Godt 35, 37).

1769—Vienna, Austria: Celebrations at the Ursuline convent in honor of the beatification of Angela Merici include special music provided by Ignaz Parhammer and the boys of the Waisenhaus, who perform the Mass with “trumpets, trombones, and flutes (Page, Convent Music 215).

1781—Vienna, Austria: Mozart’s Idomeneo utilizes trombones in the famous oracle scene, accompanying the offstage voice of Neptune (Act III Scene 10). Mozart had written to his father, “The accompaniment to the subterranean voice consists of five instruments only, that is, three trombones and two French horns, which are placed in the same quarter as that from which the voice proceeds. At this point the whole orchestra is silent” (Anderson, Letters 703). This orchestration apparently led to a disagreement with Count Seeau, intendant of the court opera at Mannheim, about the extra expense of including trombones; Mozart writes, “In addition to many other minor rows with Count Seeau I have had a desperate fight with him about the trombones. I call it a desperate fight, because I had to be rude to him, or I should never have got my way” (Anderson, Letters 706). Interestingly, there is a version in which perhaps Mozart does not get his way: a Munich performing score includes only pairs of horns, clarinets, and bassoons, with no trombones (McClelland, Ombra 79).

1787—Vienna, Austria: Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf’s opera, Die Liebe im Narrenhaus, contains the following reference to trombone: “Believe me, the devils are often much sooner moved than many human beings. There are a great many thick-eared creatures—especially among human beings—on whom not even a braying trombone can make an impression” (Jander, The ‘Kreutzer” Sonata as dialogue).

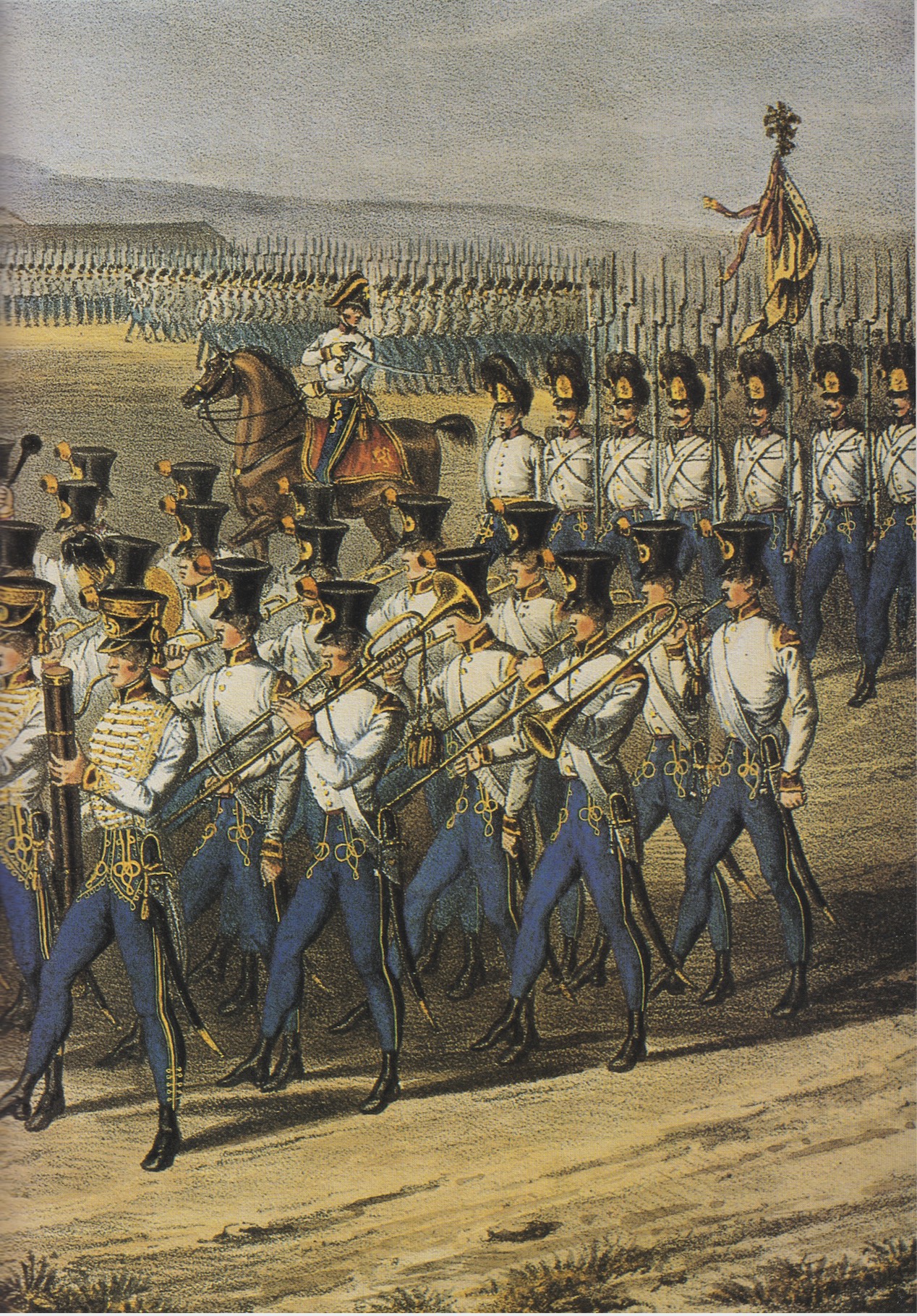

c. 1823—Vienna, Austria: A lithograph depicts a military band of the Hungarian LIR 52, marching on the glacis just outside the Vienna city wall. The depiction includes both a rear-facing trombone and a front-facing trombone (see detail below; public domain) (Brixel, Österreichs Militär Musik).

1911—Klausenburg (now Cluj, Romania): A small theater orchestra made up of musicians of the Hungarian Infantry Regiment No. 51, with theater bandmaster Franz Lamberth, includes a valve trombone (see detail below; public domain) (Brixel, Österreichs Militär Musik).

1914—Before this date, an oil painting by Alexander Pock depicts military musicians of the Hungarian Infantry Regiment No. 52 (see below image; public domain) (Brixel, Österreichs Militär Musik).

1916-1918—Znaim (Znojmo), Czech Republic: A photograph shows musicians of the Imperial & Royal Moravian Infantry Regiment No. 99, holding “Ventilposaune, Waldhorn, Armeeposaune” (see below image; public domain) (Brixel, Österreichs Militär Musik).