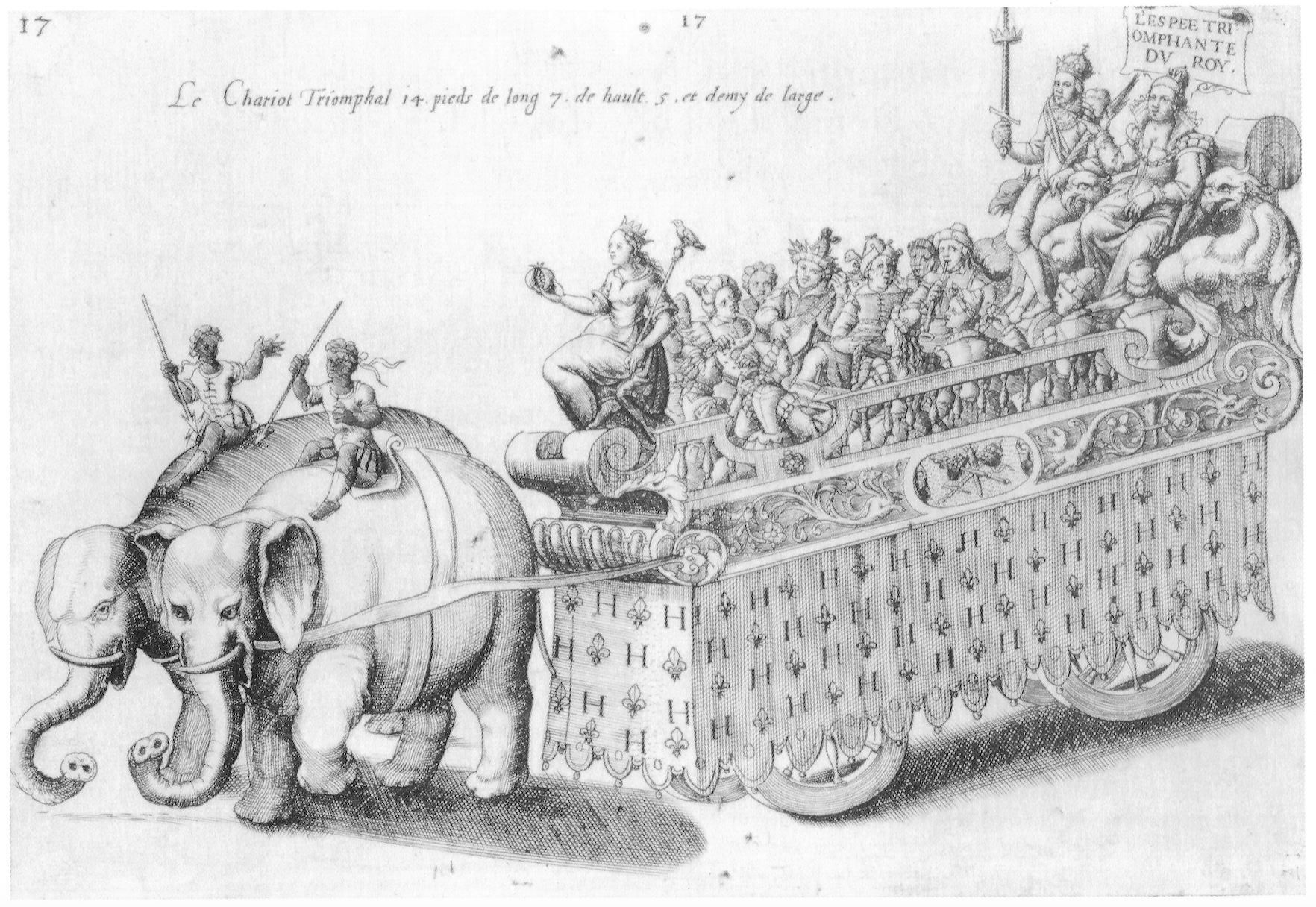

1600—Avignon, France: A triumph wagon for the entry procession of King Henry IV of France and Marie de’ Medici carries a music ensemble that includes what appears to be a serpent (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Bowles, Musical Ensembles 151).

1616—Stuttgart, Germany: Festivities celebrating the baptism of Prince Friedrich von Württemberg include serpent. First, at the service itself, the “Assum Version” festival book records that, following the baptism, a Te Deum by Salomon is sung, utilizing three ensembles: “The first, with a positive organ, four fiddles, two lutes, a small pipe and large contrabass viols, besides four singers. The other, with regal, one cornett, two trombones, a bassoon and four vocal soloists. The third also with a regal, three trombones, a serpent, in addition to four musicians” (Bowles 199-200, 207).

c. 1630—Rome, Italy: An etching from the series Figure con instrumenti musicali e boscarecci by Giovanni Battista Bracelli features a trombone and a serpent (see below image; public domain) (Falletti 107).

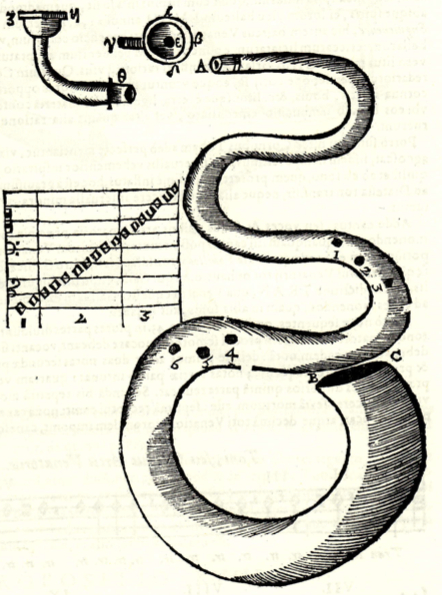

1636—Paris, France: Marin Mersenne discusses serpent and includes a woodcut of the instrument in his Harmonie universelle (see below image; public domain). Among other comments, he says the following in describing the serpent: “To accompany as many as twenty of the most powerful singers and yet play the softest chamber music with the most delicate grace notes,” “But the true bass of the cornett is performed with the Serpent, so that one can say that one without the other is a body without a soul,” “Even when played by a boy it is sufficient to support the voices of twenty robust monks,” and “It seems that the irregular distance of the holes of the Serpent makes its diapason more difficult than that of the other instruments.”

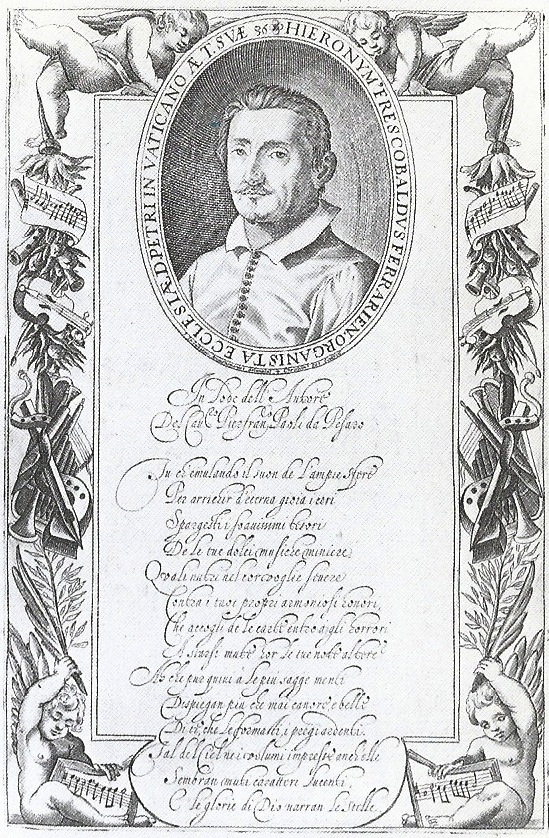

1637—Italy: A frontispiece for a collection of instrumental works by Girolamo Frescobaldi shows two serpents among the decorative clusters of instruments (see middle-left and middle-right, below; public domain) (Emilia Romagna 67).

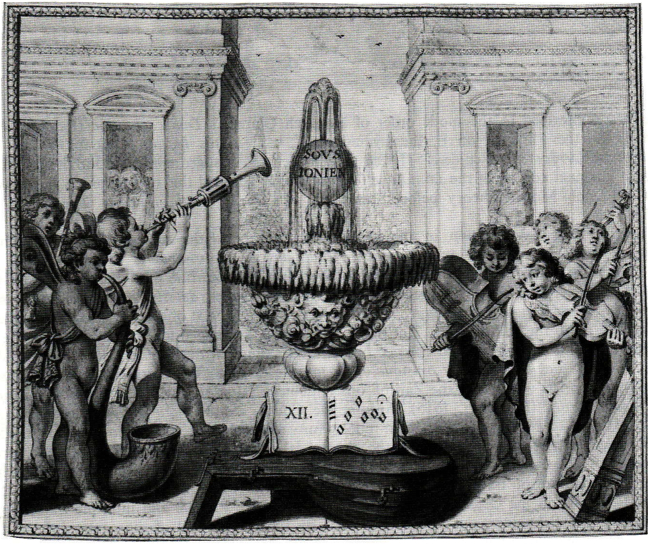

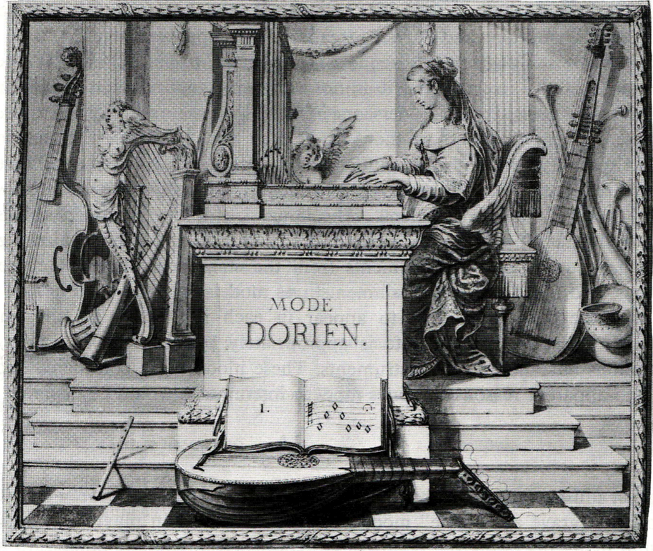

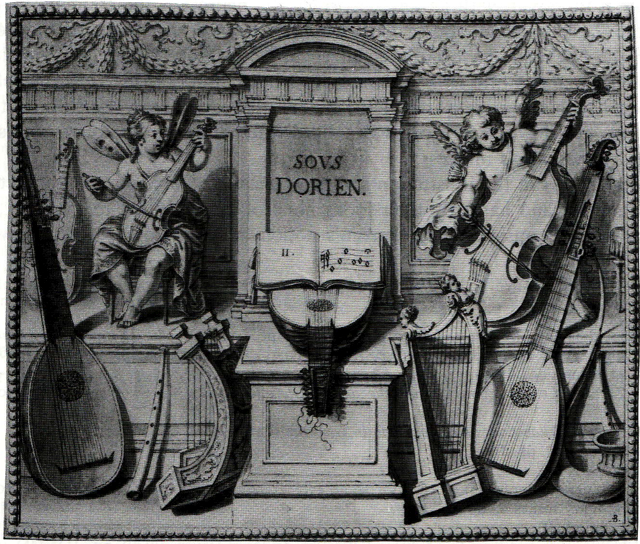

1648-1652—Denis Gaultier’s lute manuscript, La Rhetorique des dieux, features several illustrations that accompany various modes. Three of the illustrations include depictions of the serpent (see plates 19, 9, and 10, below; public domain) (David J. Buch, Coordination of Text, pl. 19, 9, 10).

c. 1660—Pierre Paul Sevin’s drawing of a performance of a mass for 4 choirs includes a serpent (see far right of image below; public domain) (Marx, The Instrumentation of Handel’s Early Italian Works).

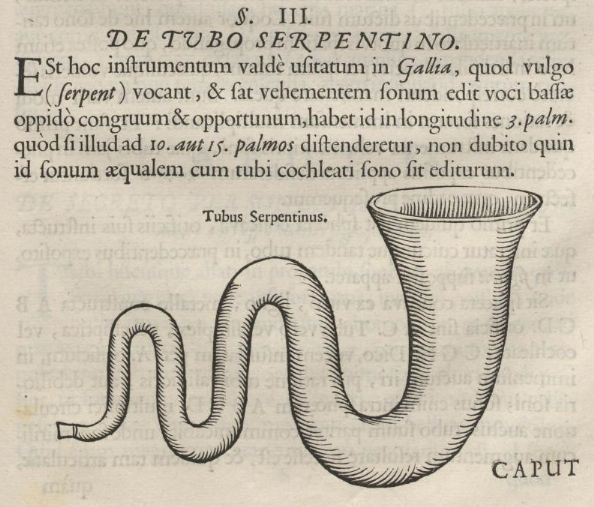

1673—Rome, Italy: Athanasius Kircher includes a print and description of the serpent in his treatise, Phonurgia nova (see below image; public domain) (source: European Cultural Heritage Online).

Late 17th century—France: An engraving by Nicolas de Larmessin from a series called Les costumes grotesques et les métiers, a series of fanciful trade costumes, includes what appears to be a serpent among numerous instruments comprising the musician’s costume (see below image; public domain).

1704-14—Saalfeld, Germany: Carlo Ludovico Castelli paints an angel playing a serpent in Saalfeld’s Schlosskapelle (see below image; public domain).

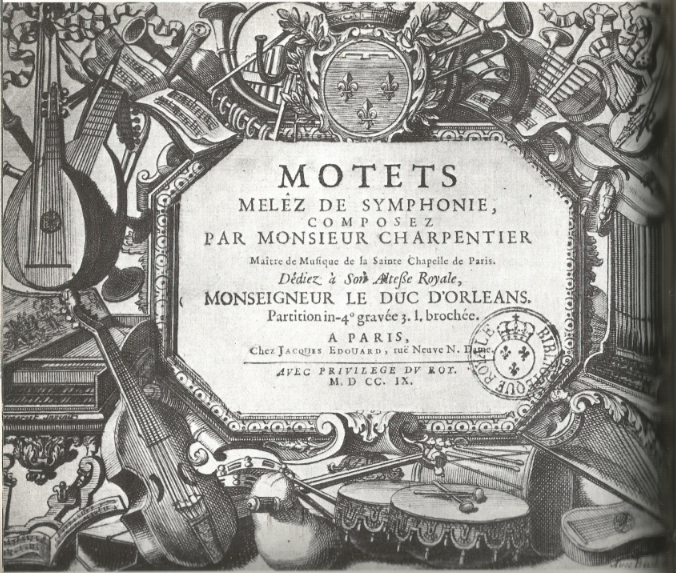

1709—Paris, France: Marc Antoine Charpentier’s Motets melez de symphonie, published posthumously, features an engraving with a cluster of instruments, including a serpent (see upper middle of below image; public domain) (Pincherle 102).

1723—Rome, Italy: An engraving from Filippo Bonanni’s Gabinetto Armonico pieno d’Instromenti depicts a serpent player (see below image; public domain).

1756—France: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in the entry on trombone in his Encyclopédie, our Dictionnaire raisonné, says the following: “It serves as the bass in all kinds of consorts of wind instruments, as do the serpent and the bassoon…” (Guion, Trombone 67).

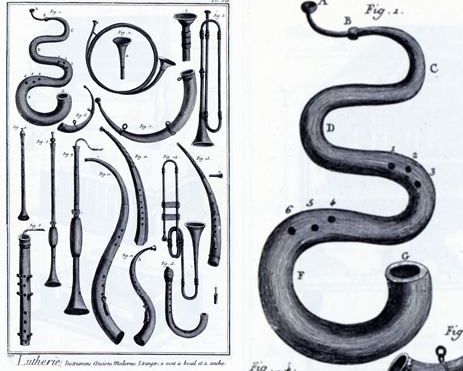

1762-1765—Paris, France: Denis Diderot includes the below graphic of the serpent in his famous Encyclopédie (see below image; public domain).

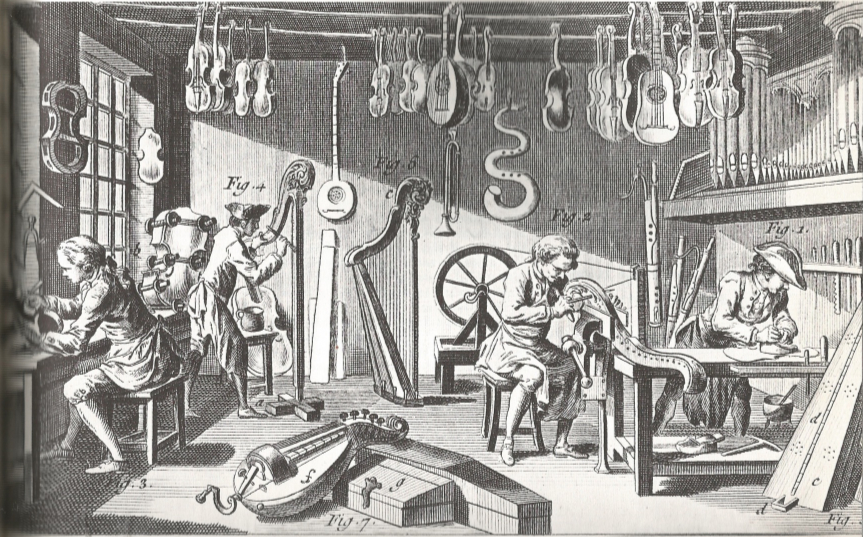

Another plate (pl. XVIII) from Diderot’s encyclopedia, this one illustrating an instrument maker’s workshop, shows a serpent hanging on the workshop wall (see below image; click on image to expand; public domain).

c. 1770—English artist Nathaniel Dance-Holland sketches Two Musicians, which features a man in powdered wig playing a serpent (see below image; public domain). Image courtesy of Tassos Dimitriadis.

1779-1781—London, England: Johann Zoffany’s portrait of the Sharp family, a musical family that holds regular concerts in London and on board their sailing barge, includes James Sharp holding a serpent (see below image; click picture for large image; public domain) (source: National Portrait Gallery, London).

1781-1854—Amsterdam, Netherlands: Military Music, a catchpenny print produced by Erve H. Rijnders, includes a serpent (see below detail; public domain) (Catchpenny Prints of the Dutch Royal Library).

1789—Paris, France: An image labeled Le Concert features a serpent performing with trio (see below image; public domain) (French National Library).

c. 1790—London, England: An engraving depicts a regiment of Foot Guards in front of St. James’s Palace. Included among the soldier-musicians is a serpent player (see below detail; public domain; Strachan, British Military Uniforms, pl. 27) (Scottish United Services Museum).

19th century—France: An anonymous painting, now held in Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (Paris) depicts a man playing serpent (see below image; public domain).

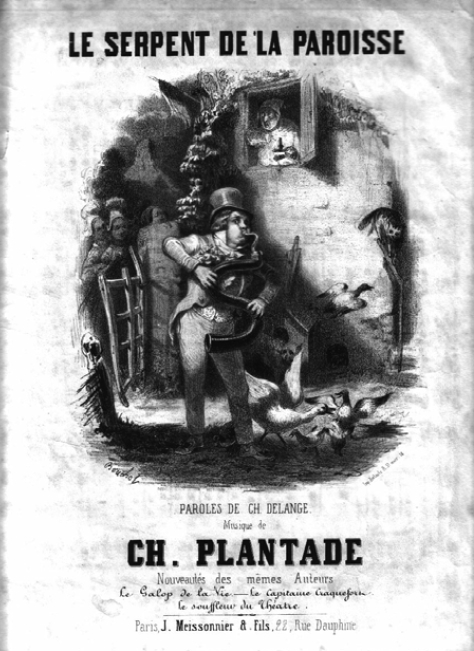

19th century—France: Le Serpent de la Paroisse, with music by Charles Plantade and text by Charles Delange, is published by J. Meissonnier & Fils in Paris (see below image; public domain).

c. 1800—Nuremberg, Germany: An image depicting Nuremberg military musicians includes a serpent player (see below image; public domain) (Nuremberg, German National Museum).

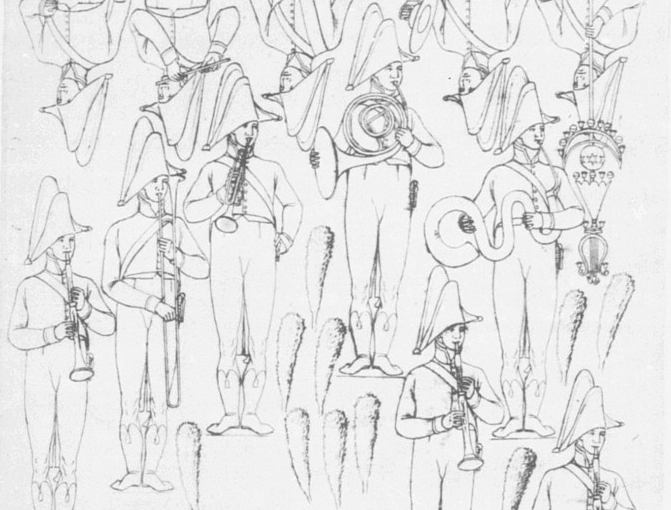

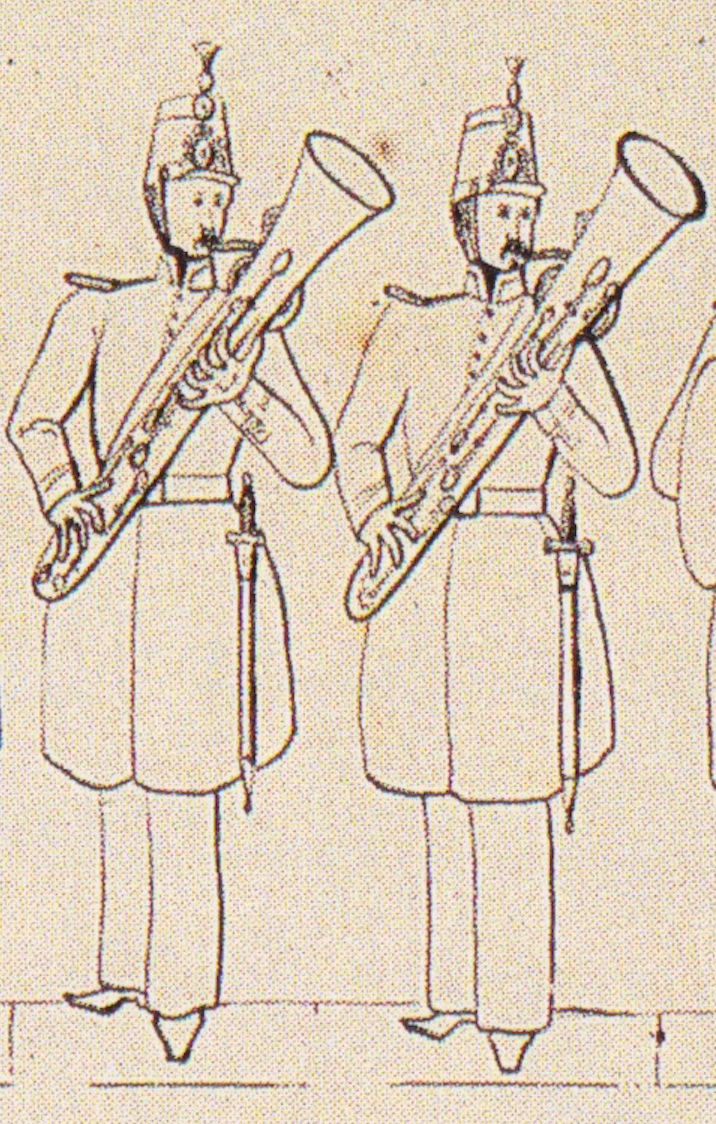

c. 1800—Germany: A print of military musicians entitled Turkische Musick der K. Baierischen Grendier Garde, now held in the German National Museum, includes a serpent (see below detail; public domain).

c. 1800—Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Philipp Jakob Döring publishes a sheet of cut-outs of military musicians that includes a man playing serpent (see below detail; public domain) (German National Museum). 1800s—France: A print entitled Macédoines—Jongleurs—Tours de force et d’adresse features a row of musicians, including a a man playing ophicleide (see below detail; public domain) (Paris, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée).

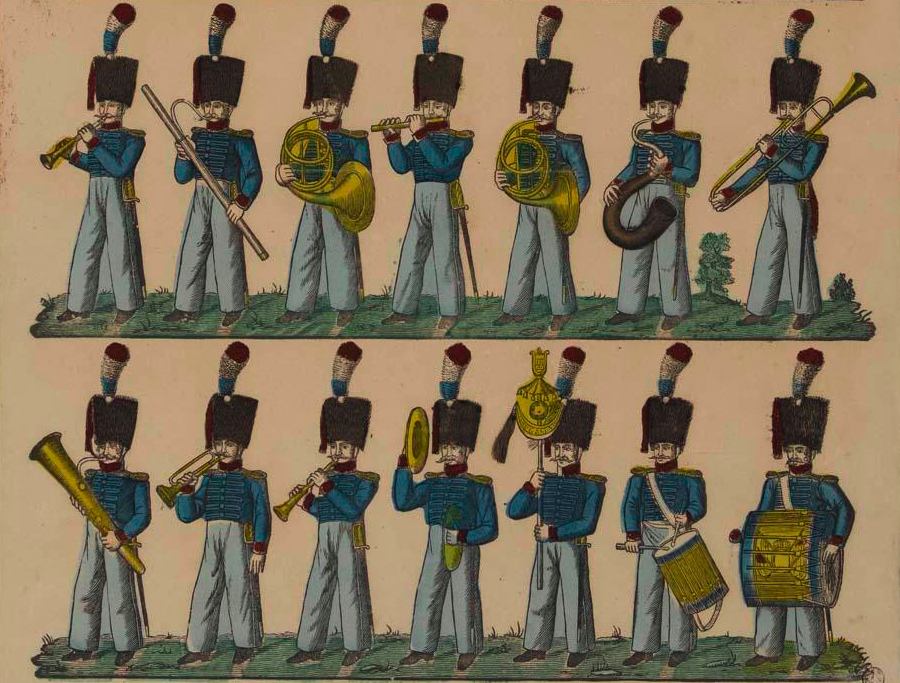

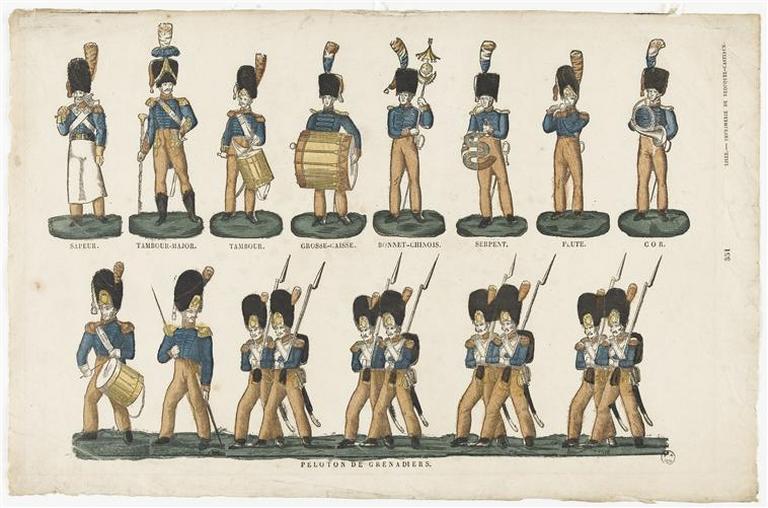

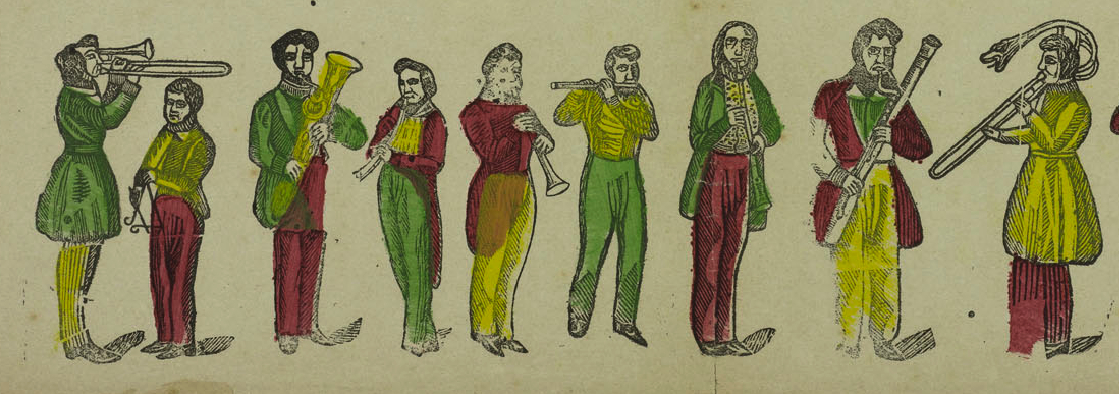

1800s—France: A print entitled Macédoines—Jongleurs—Tours de force et d’adresse features a row of musicians, including a a man playing ophicleide (see below detail; public domain) (Paris, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée). 1804-1815—France: A military illustration labeled French Napoleonic Band depicts the foot grenadiers of the 1st Regimental Imperial Army Old Guard, including a serpent player (see fourth row of image below; public domain) (Cassin-Scott and Fabb 15).

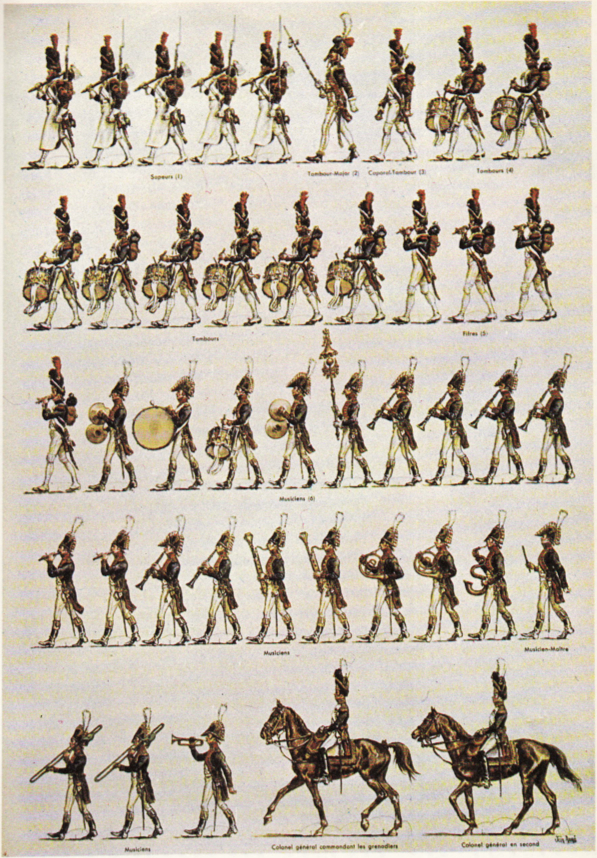

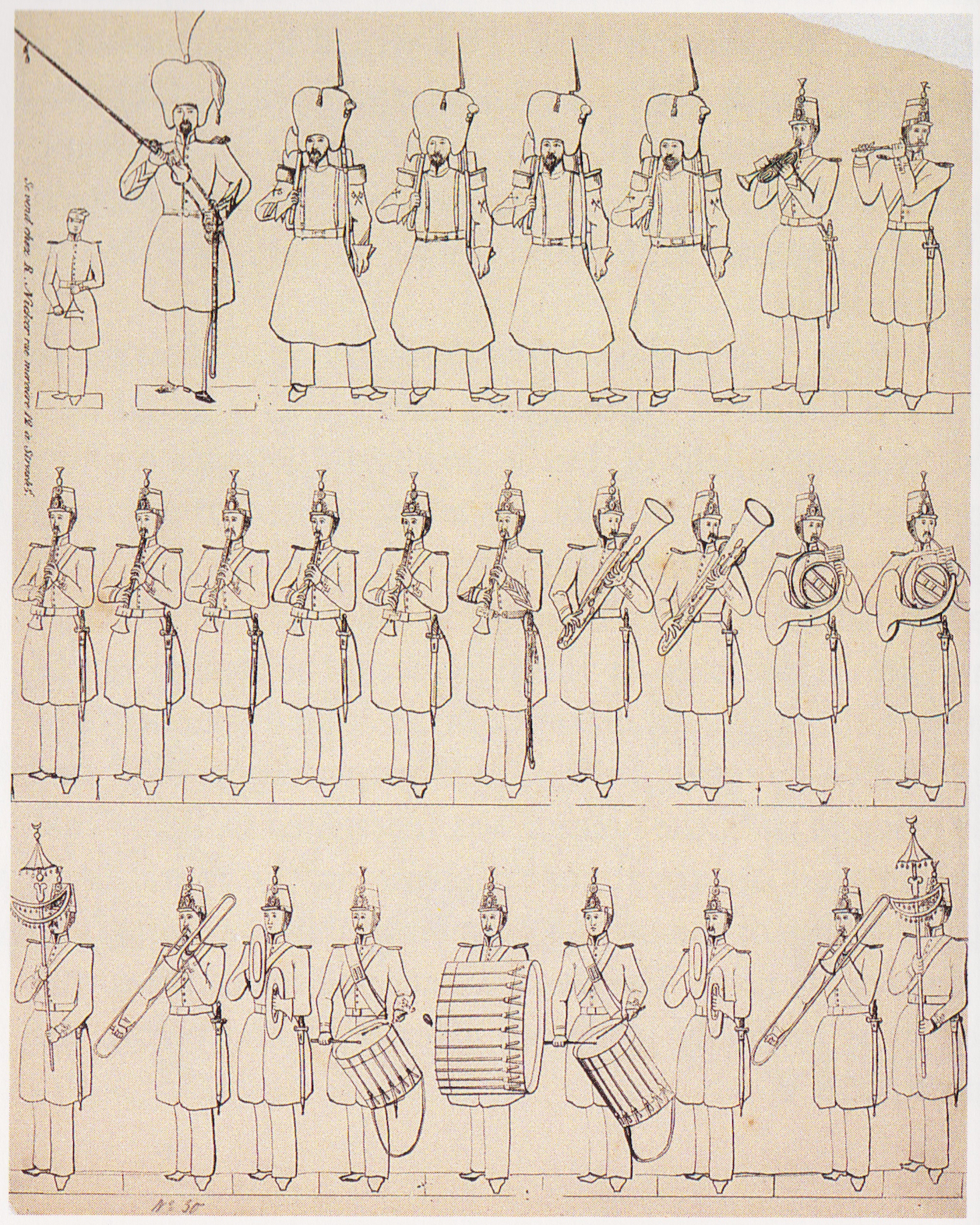

1804-1815—France: A military illustration labeled French Napoleonic Band depicts the foot grenadiers of the 1st Regimental Imperial Army Old Guard, including a serpent player (see fourth row of image below; public domain) (Cassin-Scott and Fabb 15).

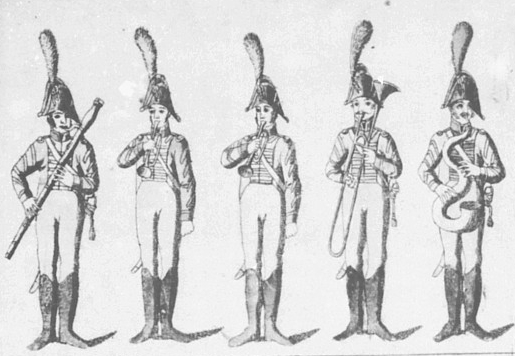

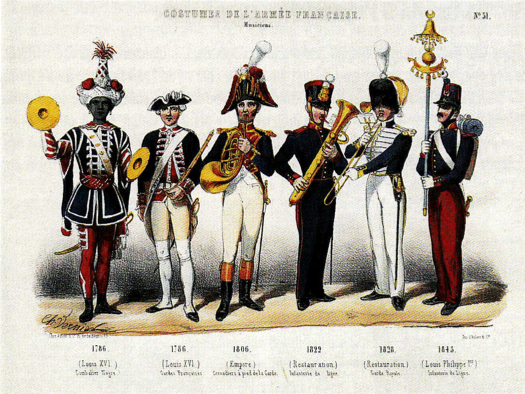

1806—France: An image depicting 7 French military musicians includes a soldier playing a serpent (see below image; public domain) (New York Public Library Digital Gallery).

1807-08—Hamburg, Germany: A painting from a series of military depictions by Christoph and Cornelius Suhr published in the 1820s in the book, Abbildung der uniformen aller in Hamburg seit den jahren 1806-1815 einquartiert gewesener truppen, portrays a group of musicians from the Catalonia Light Infantry Regiment from 1808-08 (see below image; public domain).

1807-08—Strasbourg, France: A print published by J. Gottfried Gerhardt illustrates, among a variety of soldiers from the Napoleonic army, an infantry regiment band that includes a serpent (see below image; public domain) (Ryan 21).

1809-1837—France: A printed entitled Planche de militaires, published by Jean-Baptiste Castiaux, includes a depiction of a military serpent player (see below image; public domain) (Paris, Museum of Civilization in Europe and the Mediterranean).

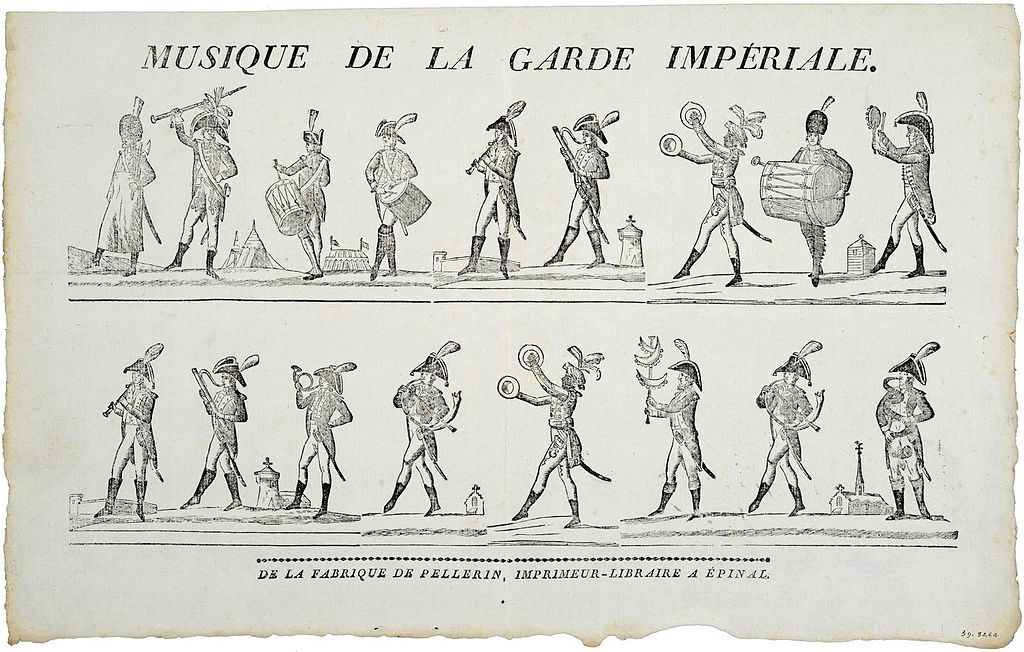

c. 1810—France: A print entitled Musique de la Garde Imperiale features military musicians from the 1st empire, including a serpent player (see bottom-right of below image; public domain).

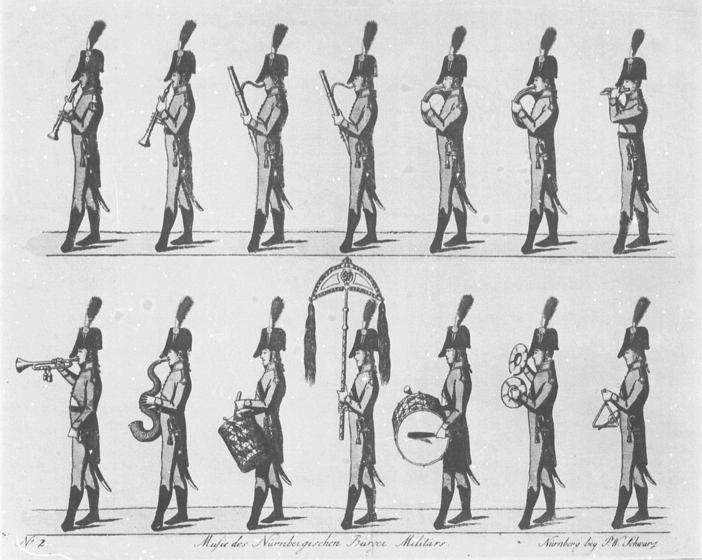

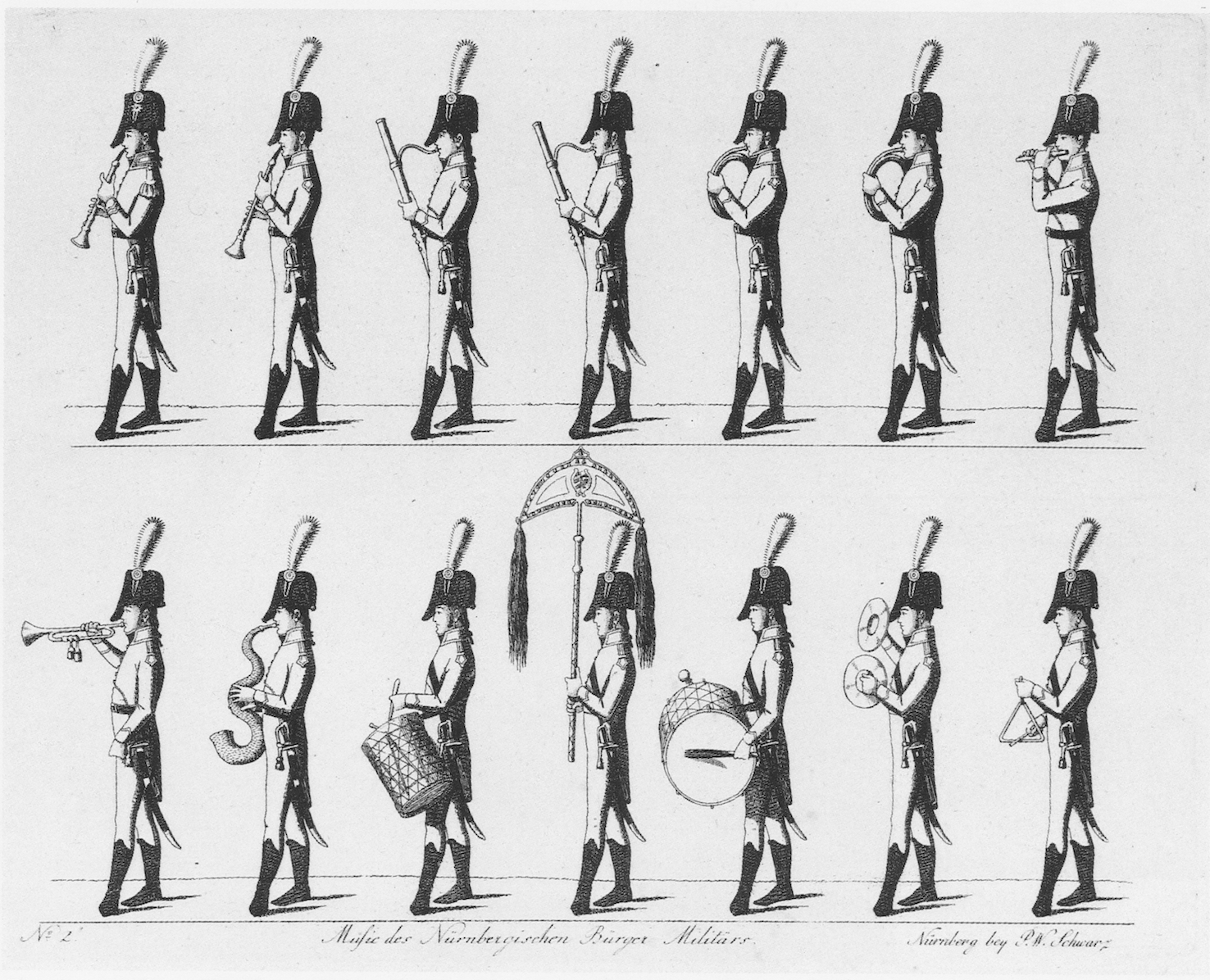

1810-18—Nürnberg, Germany: Music des Nürnbergischen Bürger Militärs, a print published by Paul Wolfgang Schwartz, includes a serpent player (see below image; public domain) (Ryan 155).

1811—Paris, France: A print published by Aaron Martinet in his series, Troupes Françaises, depicts a military serpent player. One of 296 prints in the collection, the image is titled “Garde Impériale: Musicien des Grenadiers a pied” (see below image; public domain).

1811—An illustration of the Duke of Gloucester’s Band, an ensemble associated with the 3rd regiment of the Scots Guards, includes a serpent (see below image; public domain).

1812—Paris, France: Carle Vernet, a leading French military artist, is commissioned to provide paintings of Napoleon’s new military uniforms for use by the military and its tailors. Among the series of paintings, assembled in the collection Le Grande Armée de 1812, is a picture of military musicians that includes a serpent hanging on a wall in the background (see below image; public domain) (source: wikimedia).

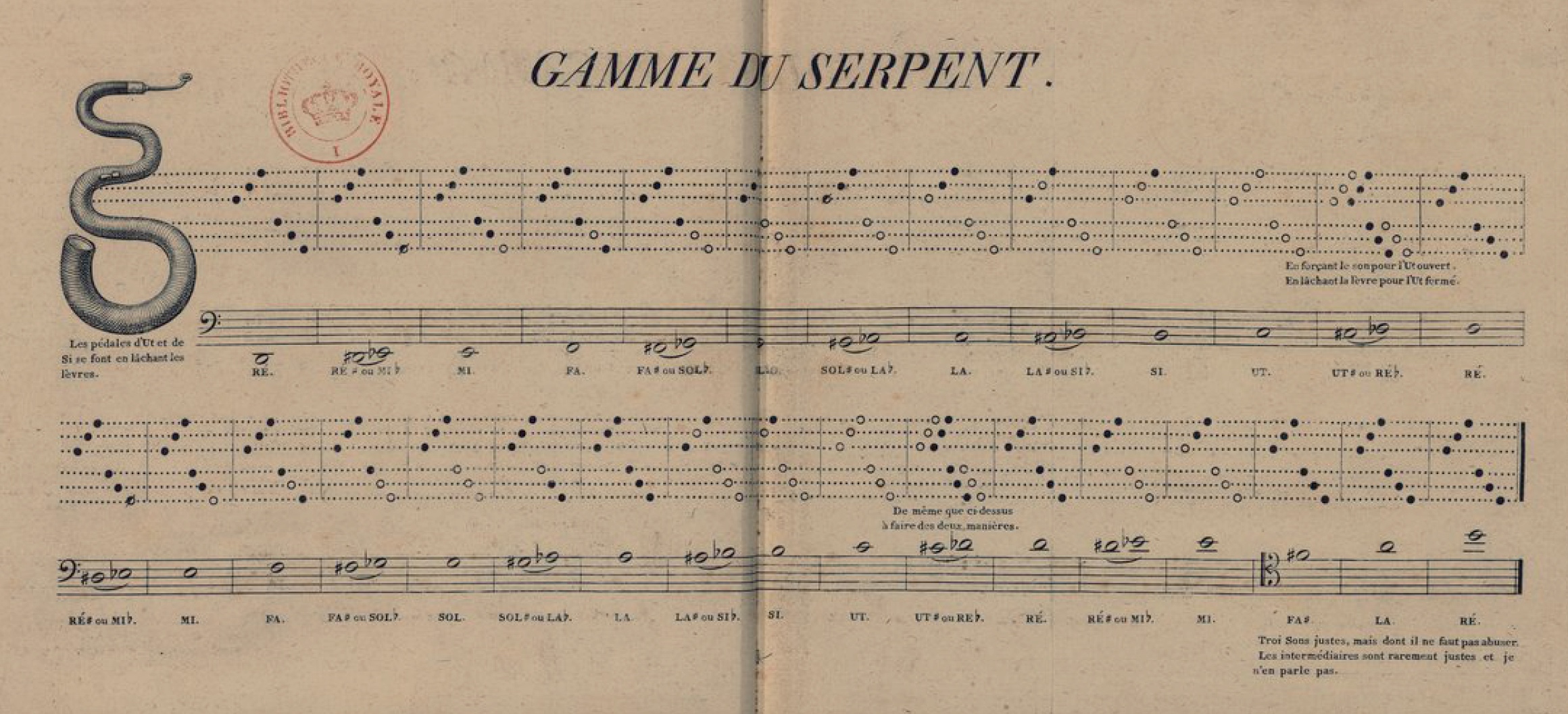

c. 1814—Paris, France: An anonymous method book, Méthode de Serpent adoptée par le Conservatoire de musique, includes, among other materials, a fingering chart for serpent (see below image; public domain) (National Library of France).

1814—Luigi Cherubini, who later becomes director of the Paris Conservatoire, writes a work for five brass instruments titled Pas redoubles et marches pour la Garde du Roi de Prusse. Scored for natural trumpet, three hand-horns, and serpent or trombone, it is conceived in the French Revolutionary military band tradition (Wallace, Brass Solo 240).

1817—Thomas Ender’s Music at Frigate Austria, probably depicting the Austrian expedition to Brazil, features a wind band that includes a serpent (see below image; public domain) (source: Google Arts & Culture, “Musica Brasilis”).

1820—Milan, Italy: A hand-colored engraving entitled Banda degli Ulani Francesi (Band of French Lancers) features a number of mounted musicians, including a pair of ophicleides (see detail below; public domain) (source: Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections).

1821—George IV, King of England, Entering Dublin, a painting by William Turner, depicts a band of cavalry musicians, including trombones and serpents (see detail and full image below; public domain) (National Gallery of Ireland).

1821—George IV, King of England, Entering Dublin, a painting by William Turner, depicts a band of cavalry musicians, including trombones and serpents (see detail and full image below; public domain) (National Gallery of Ireland).

1823—France: An image labeled Infanterie de ligne depicts a military musician playing ophicleide (see below image; public domain) (New York Public Library Digital Library).

1824—Milan, Italy: Francesco Mirecki, a Polish musician active in Italy, mentions serpent in his treatise, the earliest known Italian orchestration treatise. He considers bass trombone a useful alternative to serpent as the effective bass of the brass family (Meucci).

c. 1825—France: Pellerin, publisher of French popular prints, publishes an image titled Musique d’Infanterie Francaise, which includes both a serpent and an ophicleide—often the latter is thought of as a replacement for the former, making it somewhat unusual to include both (see below detail; public domain) (Paris, Museum of Civilization in Europe and the Mediterranean).

1825—New York: The brass section of the Independent Band consists of horns, trumpets, trombones, and serpent (Mendoza da Arce 185).

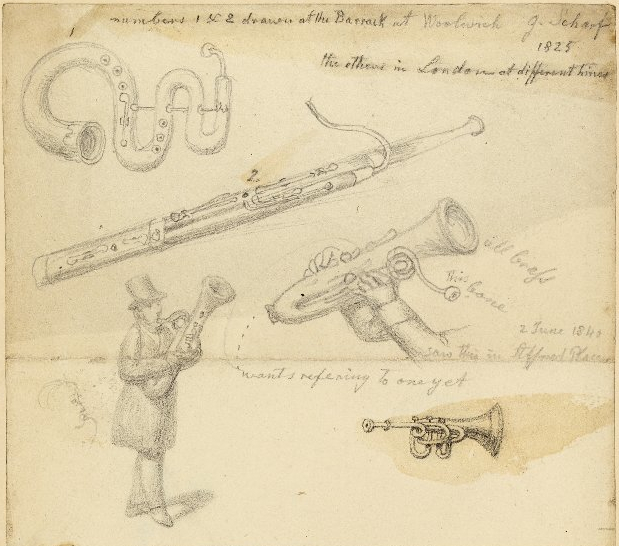

c. 1825—England: A sketch by George Scharf depicts several musical instruments, including serpent and ophicleide (see below image; public domain) (British Museum).

1825—An image, labeled Musicanti austriaci, depicts two military musicians, including an ophicleide player (see below image; public domain) (Instituto per la storia del Risorgimento italiano, Rome).

1825-50—Strasbourg, France: A watercolor by Wurtz and Pees, part of a collection of military figurines, depicts a serpent player of the regiment of mounted grenadiers of the Imperial Guard (see below image; public domain) (Paris, musée de l’Armée).

1825-50—Strasbourg, France: A watercolor by Wurtz and Pees, part of a collection of military figurines, includes depictions of 2 serpent players of the battalion of Neufchatel of 1808 (see below image; public domain) (Paris, musée de l’Armée).

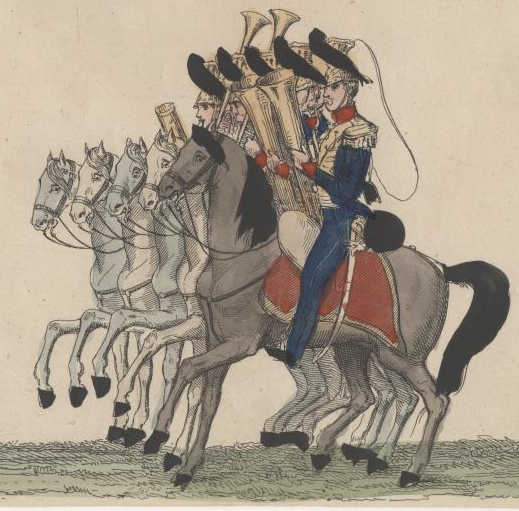

1825-50—Strasbourg, France: A watercolor by Wurtz and Pees, part of a collection of military figurines, includes a depiction of a serpent player on horseback with the 7th regiment of cuirassiers (see below image; public domain) (Paris, musée de l’Armée).

1825-50—Strasbourg, France: A watercolor by Wurtz and Pees, part of a collection of military figurines, includes a depiction of a serpent player with the musicians of the “régiment Irlandais, 1809-1811” (see below detail; public domain) (Paris, musée de l’Armée).

1825-1850—Strasbourg, France: The Wurtz and Pées family produces paper figurines of various military units. Among them are the below cavalry musicians, which include a serpent player (see below image; public domain).

1826—A drawing by George Scharf features military musicians playing various instruments, including both serpent and trombone. The writing below the drawing reads, “At the Marine Officers Mess Room, at Woolwich, during Dinner” (see below image; public domain) (British Museum).

1828—Great Britain: A military image features a British serpent player in full military garb (see below image; public domain) (New York Public Library Digital Gallery).

c. 1829—Mainz, Germany: Artist Joseph Scholz depicts a group of 4 military musicians of the Prussian Army on horseback in an image titled Preussisches Heer–Garde Artillerie (see below image; public domain) (Ryan, Paper Soldiers).

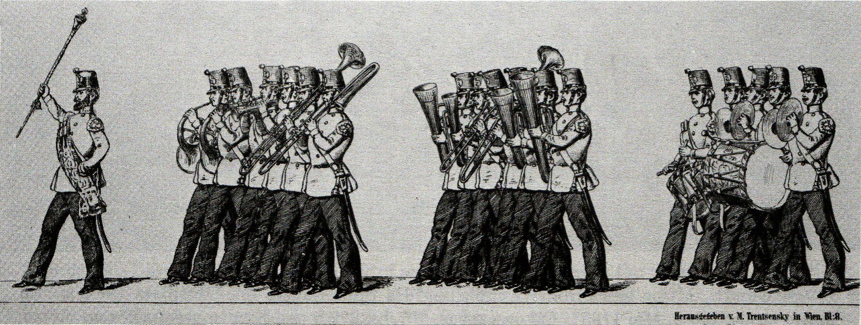

c. 1830—Vienna, Austria: K.k. Österreichischer Militair Leichen-Conduct, lithograph no. 8 from a series edited by Michael Tretsentsky, shows a military band that includes multiple ophicleides (see below image; public domain) (Pirker).

c. 1830—France: Jeune musician a l’ophicleide, an anonymous painting, shows a young French musician with ophicleide in the uniform of the Garde nationale (see below image; public domain) (Musée de l’armée, Paris).

1830—France: Garde Imperiale: Regiments des Grenadiers a pieds, an image created by G. David in 1830 but meant to depict 1804, includes a military serpent player (see below image; public domain).

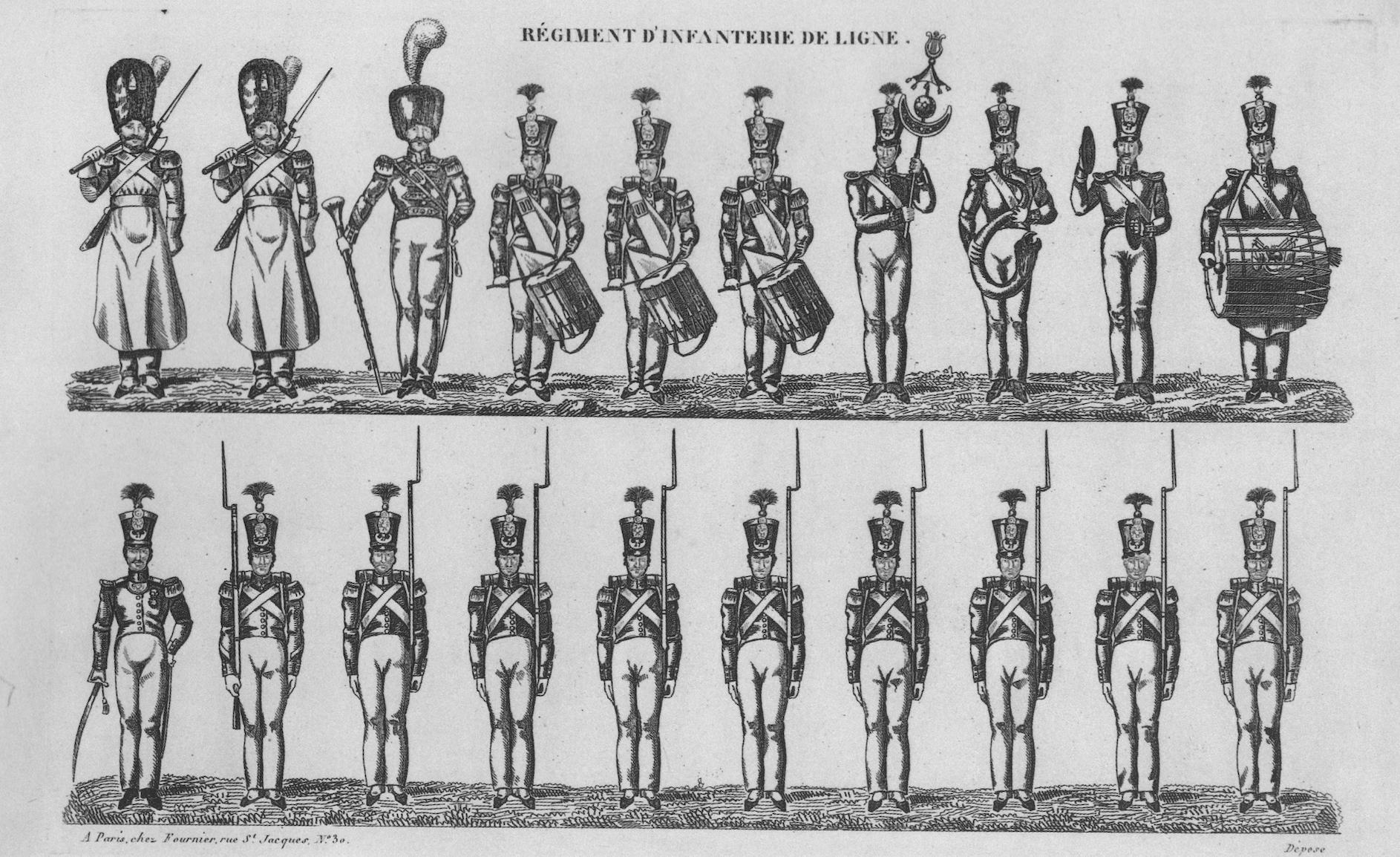

1831-1870—Paris, France: Regiment d’Infanterie de Ligne, a print published by Fournier, features a serpent with a zoomorphic bell (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Ryan 121).

1833-1900—Turnhout, Belgium: A catchpenny print entitled Harmonie, probably published by Glenisson and Van Genechten, features musicians playing various instruments, including an ophicleide (see below detail; public domain) (Catchpenny Prints of the Dutch Royal Library).

c. 1835—Paris, France: Un Serpent de Paroisse (a parish serpent), a satirical lithograph by Delaunois, is published in a Paris periodical (see below image; public domain) (source: Douglas Yeo, personal communication).

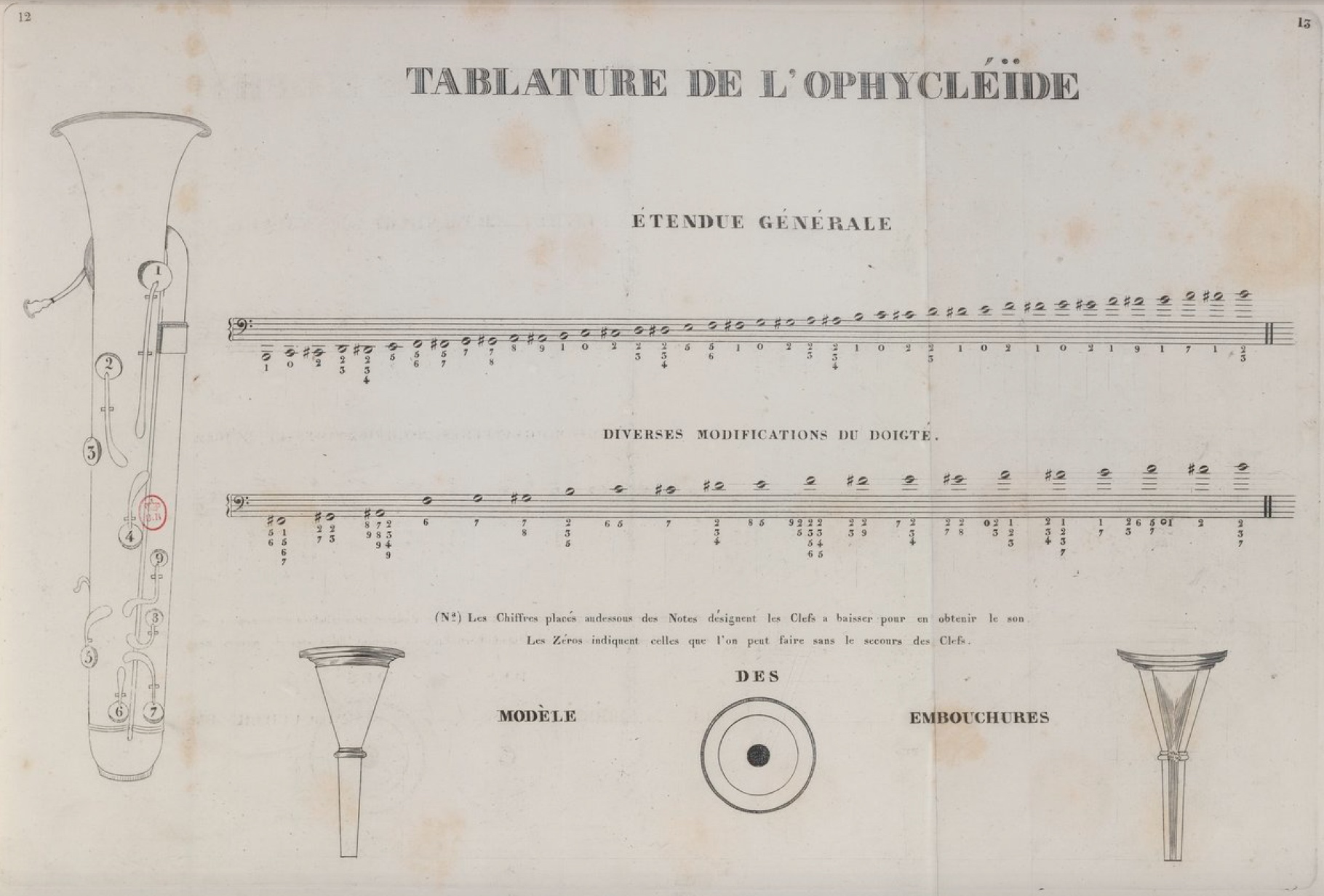

c. 1835—France: Victor Cornette writes his Methode d’Ophycleide Alto et Basse. It includes a print signed by V. Bretonnierie (dated 1835) and a fingering chart (see below 2 images; public domain).

1840—Epinal, France: An engraving entitled Musique d’Amateurs, published by Pellerin, includes an ophicleide among 27 figures with various musical instruments (see below image; click picture for larger version; public domain).

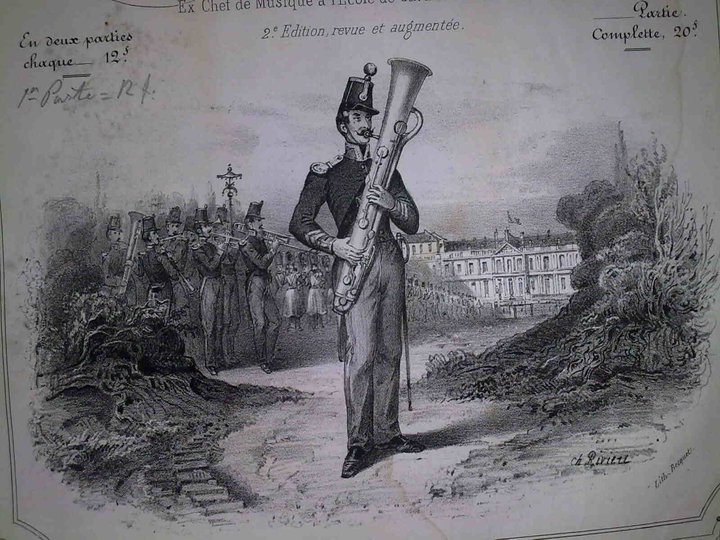

c. 1840—Paris, France: Félix Vobaron’s New Method for Bass Ophicleide includes the below depiction of a military band featuring an ophicleide in the foreground with what may be another ophicleide in the background (far left) (see below image; public domain).

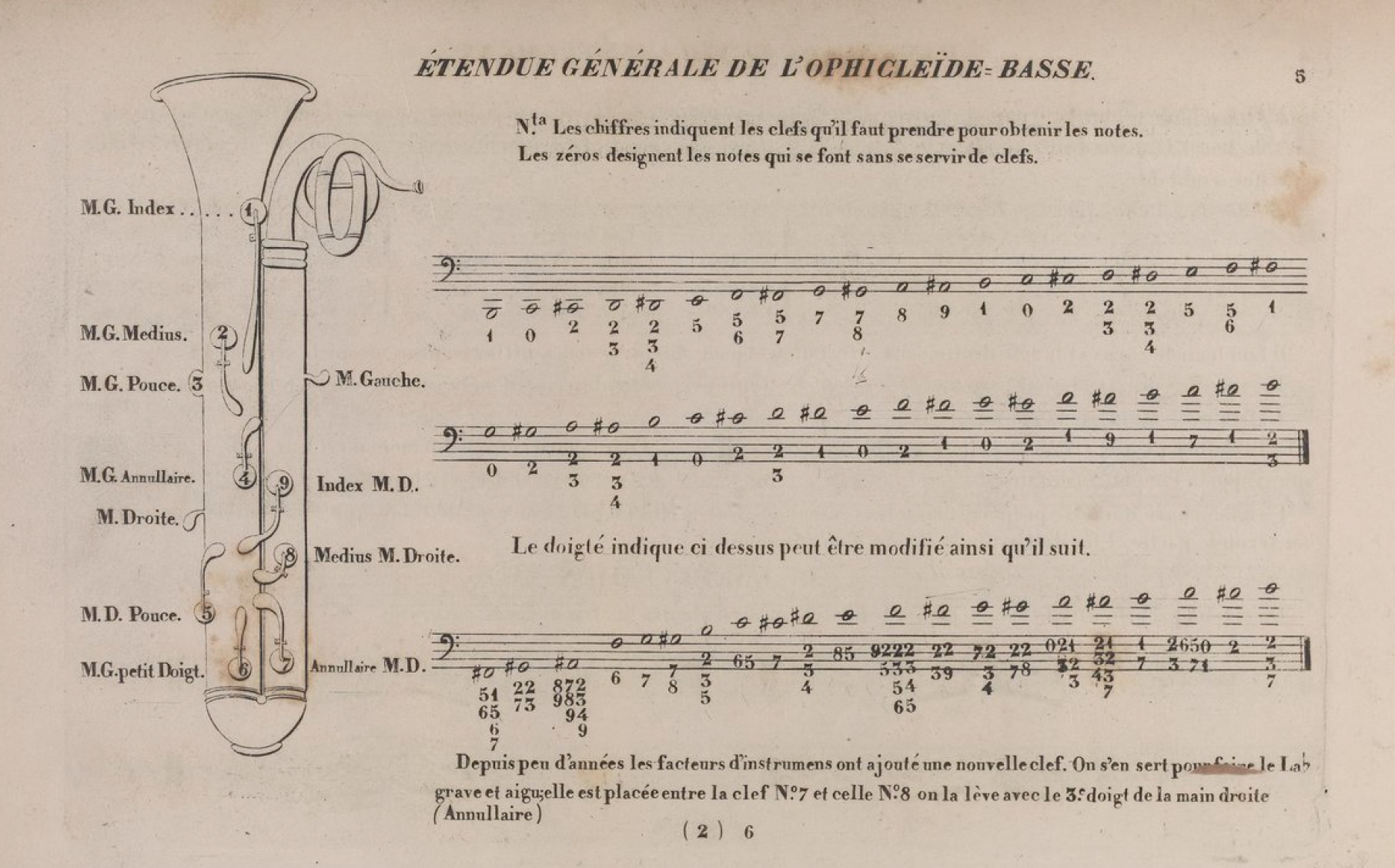

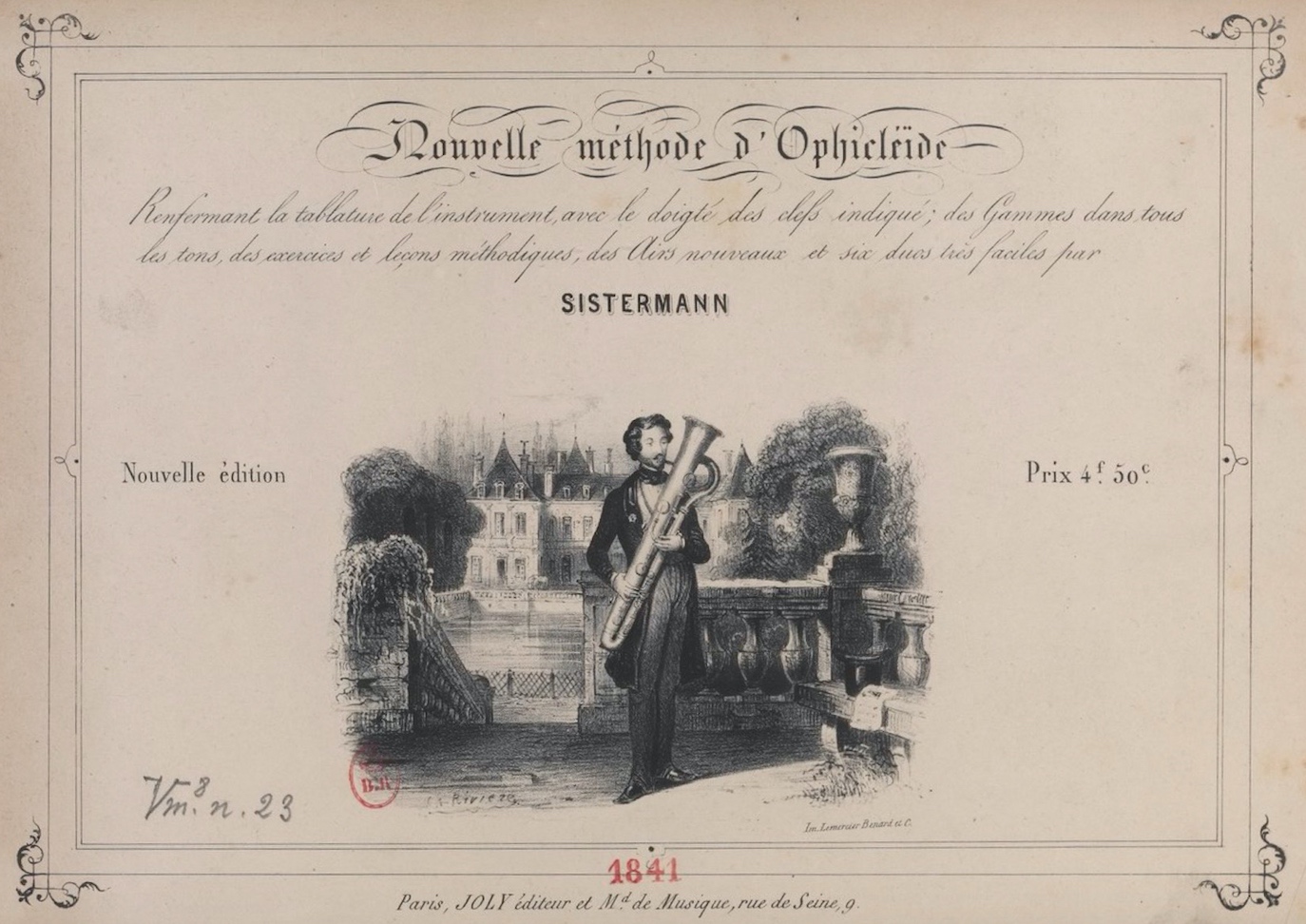

1841—Paris, France: Sistermann’s ophicleide method, Nouvelle méthode d’ophicléide, is published by Joly (see cover and fingering chart, below; public domain) (source: French National Library).

1842—Mannheim, Germany: Berlioz, on a tour of Germany, visits Mannheim, where he uses a valve trombone as a substitute for ophicleide: “There is no ophicleide; Lachner [the regular conductor] had attempted to devise a substitute for this instrument, which is used in all modern scores, by having a valve trombone made with a compass extending to bottom C or B. In my opinion it would have been simpler to send for an ophicleide and much better from the musical point of view, as the two instruments have little in common” (Berlioz-Cairns 288).

1842—Leipzig, Germany: Berlioz, on a tour of Germany, visits Liepzig. He reports in his Memoirs that “the ophicleide, or rather the meager brass object masquerading under that name, bore no resemblance to the French variety, having practically no tone,” so it was “replaced, after a fashion, by a fourth trombone” (Berlioz-Cairns 300).

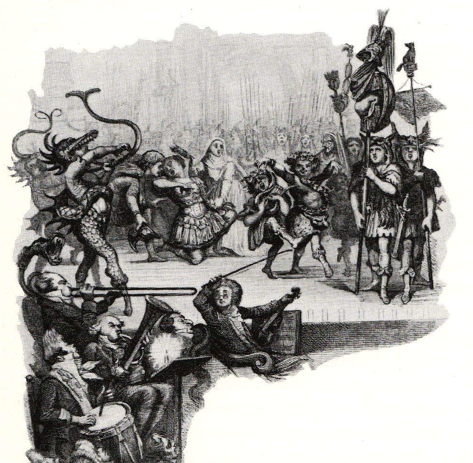

1843—France: A depiction of a theatre orchestra includes what may be an ophicleide. The image is printed in “La Parodie de la Vestale,” Chants et Chansons Populaires de la France II, 1843 (see below image; public domain) (London, British Library; Remnant, Musical Instruments of the West 216). 1843—Berlin, Germany: Hector Berlioz visits Berlin, where he hears 2 bass trombones in the opera orchestra. Complaining that there are none in Paris, he says, “Parisian musicians refuse to play an instrument that is so tiring to the chest. Prussian lungs are evidently more robust than ours.” He is not, however, impressed with the balance of the trombone section there; he reports: “Their combined volume of tone is so great as to obliterate the alto and tenor trombones playing the two upper parts. The aggressive tone of one bass trombone would be enough to upset the balance of the three trombone parts as written by composers nowadays. But there being no ophicleide at the Berlin Opera, they give the part to a second bass trombone. The effect of having two of these formidable instruments one above the other (the ophicleide part being frequently written an octave below the third trombone) is disastrous. You hear nothing but the bottom line; even the trumpets are all but drowned. When I came to give my concerts I found that the bass trombone was much too prominent—although in the symphonies I was using only one—and had to ask the player to sit so that the bell of the instrument was facing into his stand, which acted as a sort of mute, while the alto and tenor trombonists stood up to play with their bells pointing over the top of their stands. Only in this way could all three parts be heard” (Macdonald 213).

1843—Berlin, Germany: Hector Berlioz visits Berlin, where he hears 2 bass trombones in the opera orchestra. Complaining that there are none in Paris, he says, “Parisian musicians refuse to play an instrument that is so tiring to the chest. Prussian lungs are evidently more robust than ours.” He is not, however, impressed with the balance of the trombone section there; he reports: “Their combined volume of tone is so great as to obliterate the alto and tenor trombones playing the two upper parts. The aggressive tone of one bass trombone would be enough to upset the balance of the three trombone parts as written by composers nowadays. But there being no ophicleide at the Berlin Opera, they give the part to a second bass trombone. The effect of having two of these formidable instruments one above the other (the ophicleide part being frequently written an octave below the third trombone) is disastrous. You hear nothing but the bottom line; even the trumpets are all but drowned. When I came to give my concerts I found that the bass trombone was much too prominent—although in the symphonies I was using only one—and had to ask the player to sit so that the bell of the instrument was facing into his stand, which acted as a sort of mute, while the alto and tenor trombonists stood up to play with their bells pointing over the top of their stands. Only in this way could all three parts be heard” (Macdonald 213).

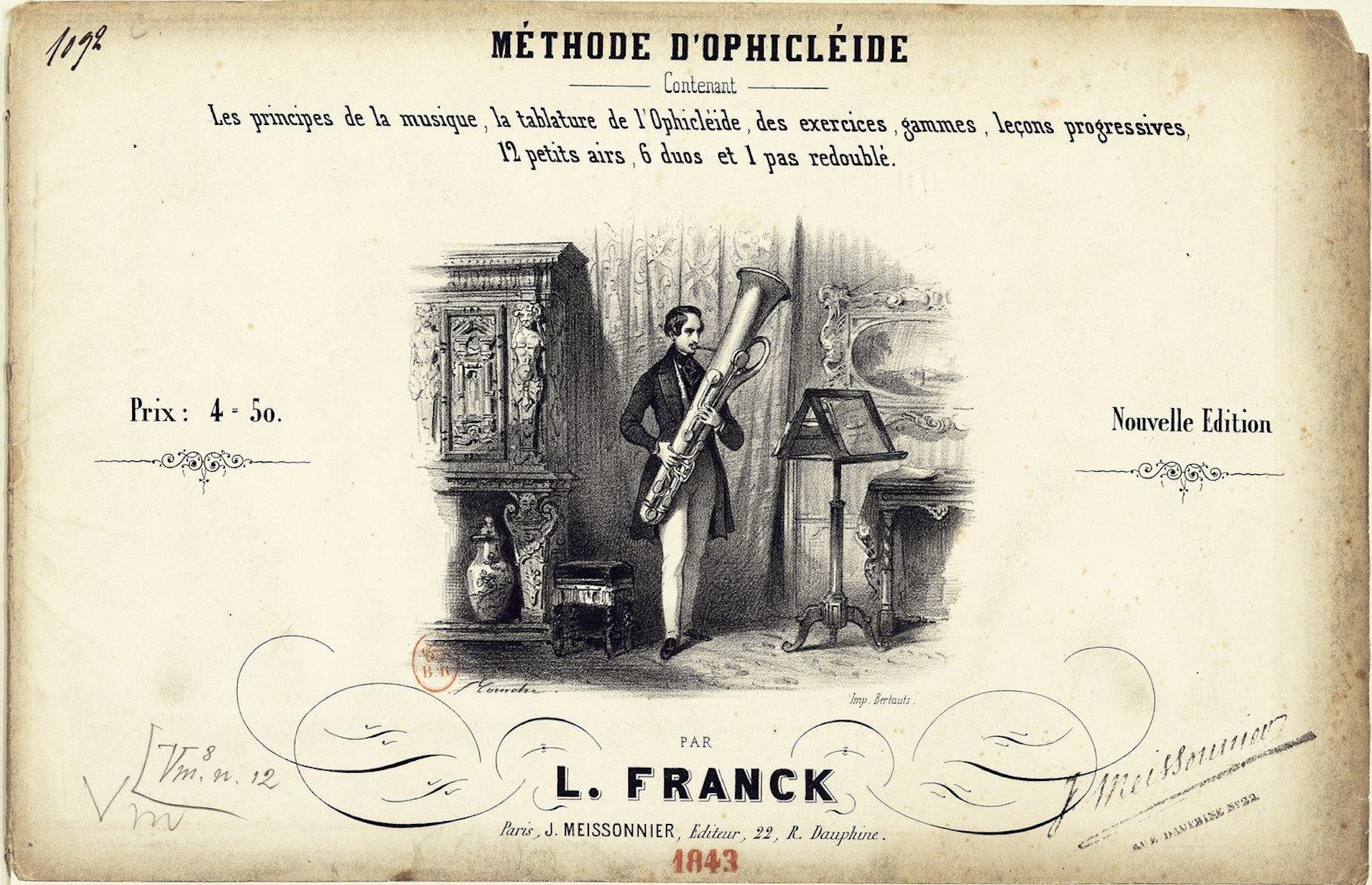

1843—Paris, France: L. Franck’s Méthode d’ophicléide is published by J. Meissonnier (see below image; public domain) (National Library of France).

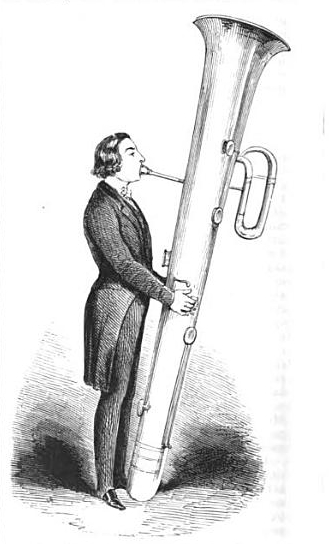

1843—London, England: A cartoon in Punch magazine featuring an enormous ophicleide accompanies the complaint, “The ophycliedes [sic] get bigger and bigger each day, and it is impossible to tell at what pitch of monstrous magnitude they will ultimately arrive. We shall not be surprised if they finally form the abodes of the men who play them: an accommodation which will be very valuable to perambulating musicians at the seasons of the various Festivals” (see below image; public domain) (vol. IV, p. 235). 1844—A depiction of Prospere (Jean Prospere Guivier), one of the great ophicleide players of the 19th century, shows him playing a “monster” ophicleide at Hanover Square Rooms. It is later reprinted in the Musical Times in June, 1894 (see below image; public domain).

1844—A depiction of Prospere (Jean Prospere Guivier), one of the great ophicleide players of the 19th century, shows him playing a “monster” ophicleide at Hanover Square Rooms. It is later reprinted in the Musical Times in June, 1894 (see below image; public domain). 1844—Boston, Massachusetts: Simon Knaebel publishes brass quartet arrangements for 2 bugles in B-flat, trombone, and ophicleide in Keith’s Collection of Instrumental Music (Dudgeon, Keyed Bugle 173).

1844—Boston, Massachusetts: Simon Knaebel publishes brass quartet arrangements for 2 bugles in B-flat, trombone, and ophicleide in Keith’s Collection of Instrumental Music (Dudgeon, Keyed Bugle 173).

1844—Milan, Italy: Fermo Bellini’s Teoriche musicali discusses the use of trombone with ophicleide: “The modern custom, adopted by some composers, of forming a quartet consisting of three trombones and an ophicleide does not seem very sensible, given that the tone colour of the trombones, so dominant and in high relief, is very different from that of the ophicleide; it would be better for this instrument to double the bottom line, or else to find some way to give the trombones a good cantabile bass whenever they are on their own” (Meucci).

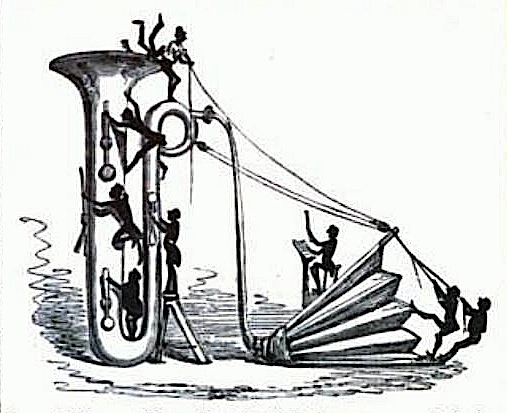

1844—France: An illustration by J. J. Grandville in Un autre Monde depicts an ophicleide gone awry, as described by Grandville: “An accident marked the end of the concert. During the fireworks in D, where the fugue ended smorzando in a sweet and dreamy melody, an ophicleide, overloaded with harmony, suddenly exploded like a bomb, launching the blacks, the whites, the grupetti of sharps, eight- and sixteenth notes; the clouds of musical smoke and the flames of melody were dispersed into the air. Many dilettantes had their ears blown out, while others were injured by the shrapnel of the F and G clefs. Measures have been take to ensure that such an accident does not happen again” (see below image; public domain).

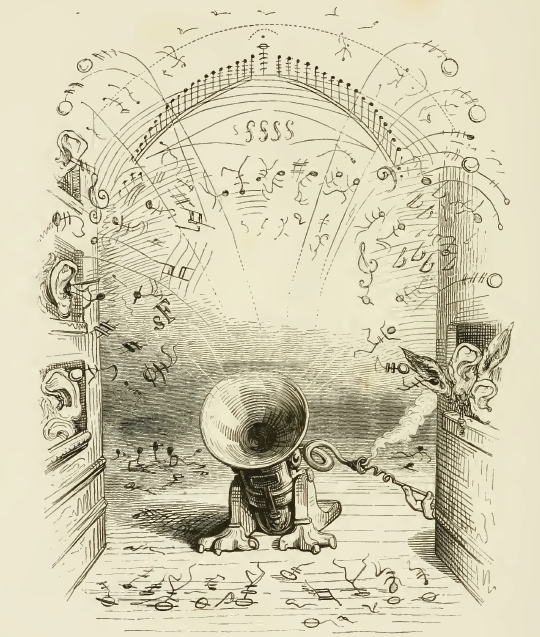

1844—France: Another illustration by J. J. Grandville in Un autre Monde depicts a Concert of Steam (Concert a la vapeur) in response to a prediction about steam changing the world. Included in the “steam orchestra” is an ophicleide (see below image; public domain) (Fromrich 133).

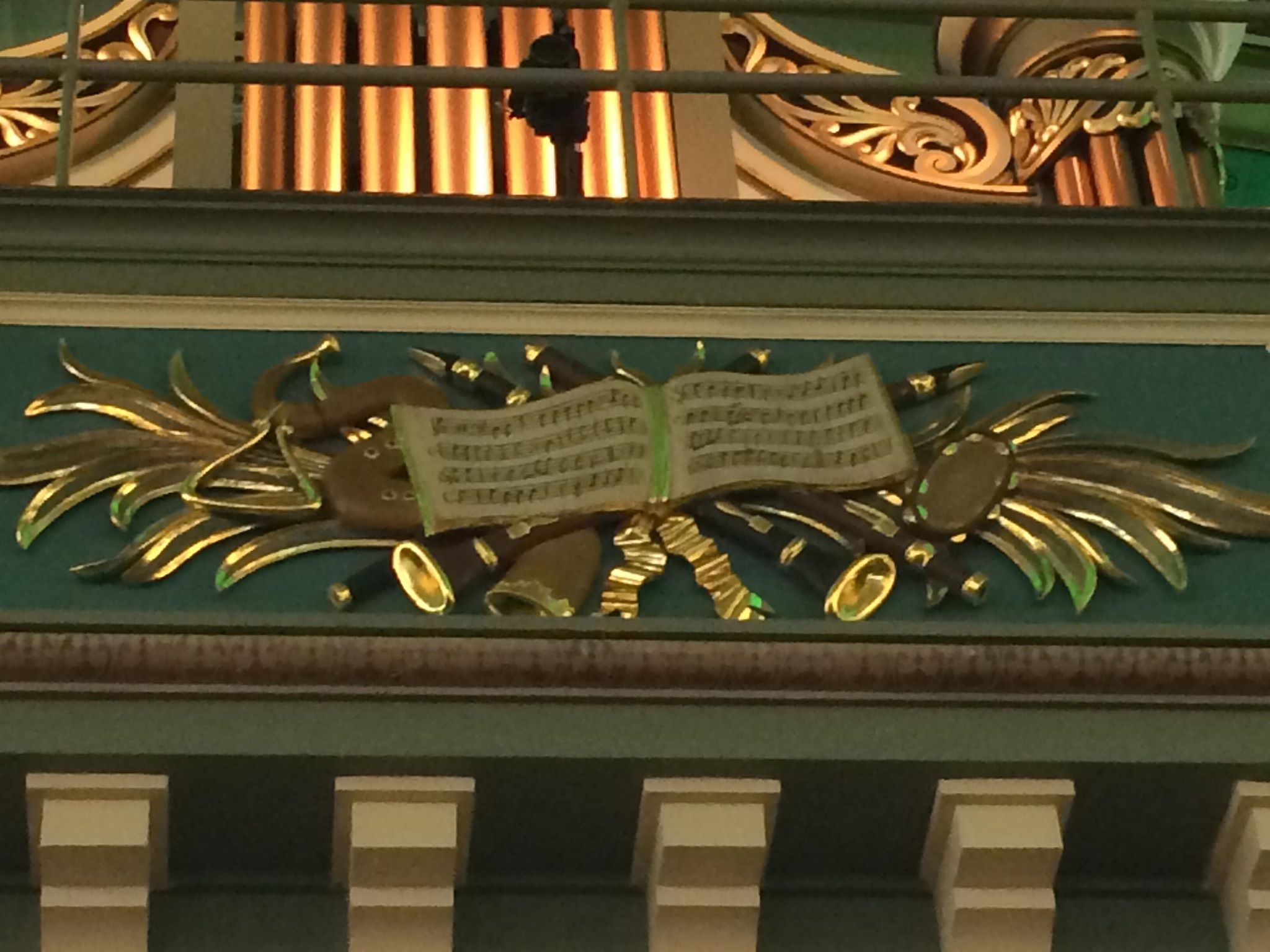

1844-50—Boucherville, Québec, Canada: Interior decorations by Louis-Thomas Berlinguet and his son Louis-Favien in Église Sainte-Famille (Church of the Holy Family) include 2 different depictions of serpents, both set in trophies, or decorative clusters of instruments (see below image; special thanks to Maximilien Brisson).

c. 1845—Paris, France: An illustration by Charles Vernier, Uniforms of the French Army, Musicians, features numerous military musicians, including a soldier with what appears to be an ophicleide (see below image; public domain) (Mardaga 119).

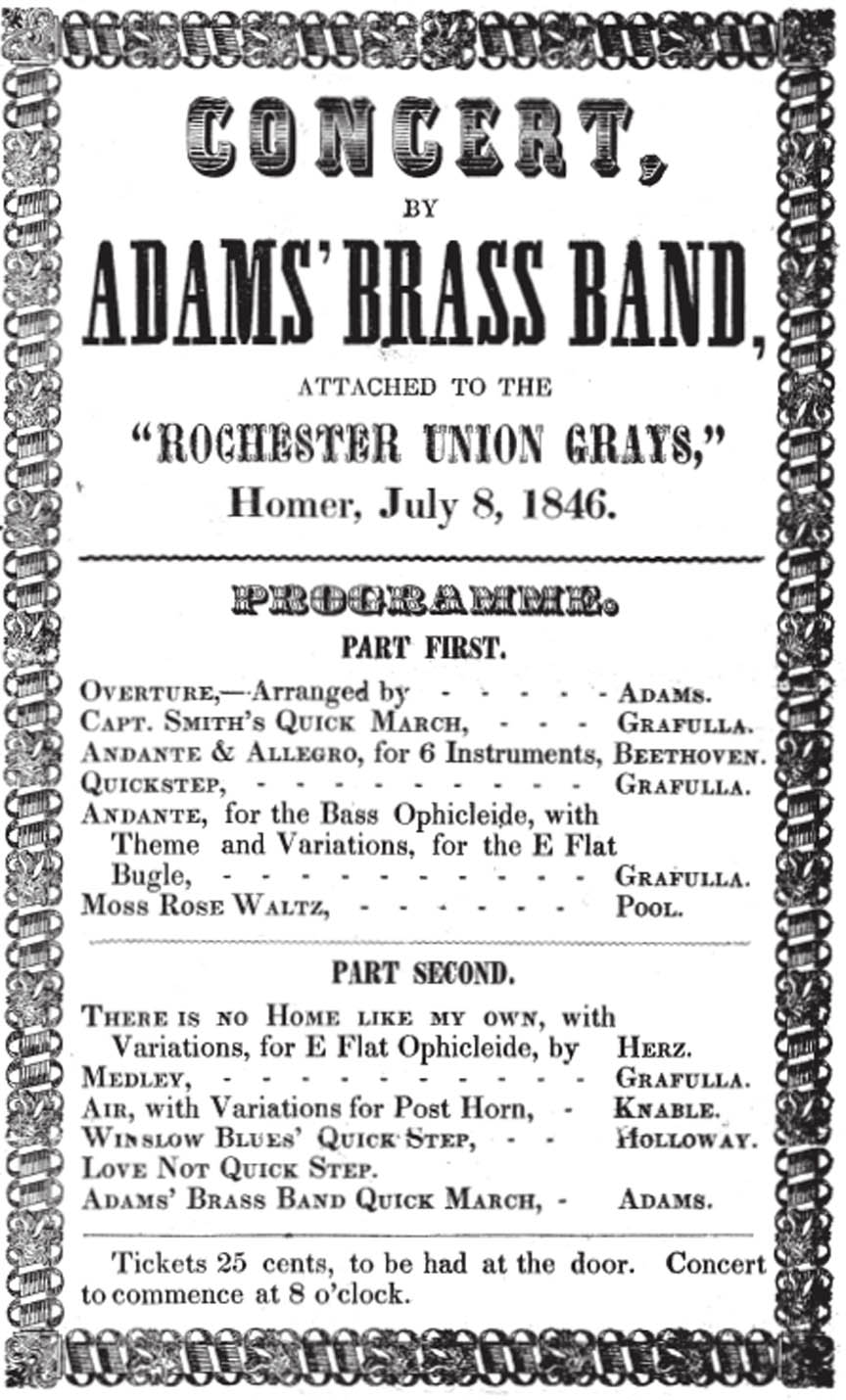

1846—A concert poster for “Adams’ Brass Band attached to the ‘Rochester Union Grays'” indicates two different ophicleide solos (see below image; public domain).

1846—London, England: “A Sunday Band of Hope,” a brief article in Punch magazine about bands playing on Sunday, includes a graphic of a bandsman sitting down by his ophicleide for a drink (see below image; public domain) (p. 189).

1846—Paris, France: A caricature by J.J. Grandville depicts Berlioz conducting a monstrous orchestra that includes a giant ophicleide (see below image; public domain) (source: wikimedia commons). The original version of the image, published in a Paris newspaper in 1845, was black and white and did not include the large ophicleide on the top-right. The version below was published in Louis Reybaud’s novel, Jérome Paturot a la recherche d’une position sociale, with a caption reading, “Fortunately the hall is solid…it can handle the strain.”

c. 1847—Paris, France: A hand-colored lithograph showing a caricature by François Bouchot, number 6 in a series called Les bonnes Tetes Musicales, appears in the journal Le Charivari. The title shown at the base of the print is Etudes consciencieuses sur de nouveaux instrumens de M. Sax (see below image; public domain).

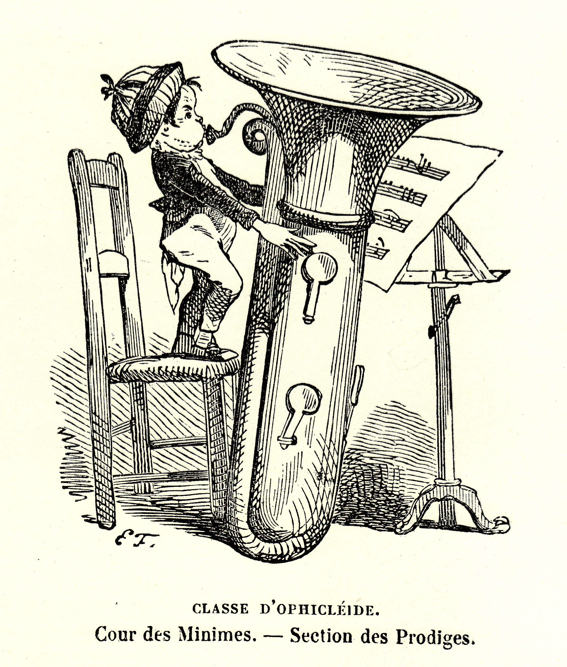

1847—France: A print depicting a religious procession (Procession of the Virgin) features an an ophicleide as the only instrumentalist (see bottom-left of below image; public domain) (Paris, Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilization). 1847—Paris, France: Eugene-Hippolyte Forest’s satirical print, The Conservatoire, Classe d’Ophicléide, is published in Paris Musical. The subtitle reads “Court of the Tiny Ones–Section of the Prodigies” (see below image; public domain) (Fromrich, 139).

1847—Paris, France: Eugene-Hippolyte Forest’s satirical print, The Conservatoire, Classe d’Ophicléide, is published in Paris Musical. The subtitle reads “Court of the Tiny Ones–Section of the Prodigies” (see below image; public domain) (Fromrich, 139).

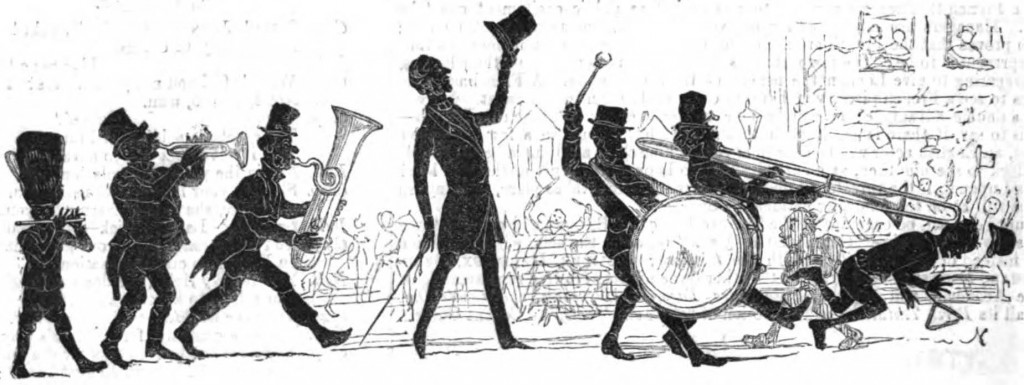

1848—London, England: A cartoon published in Punch magazine includes an ophicleide among members of a band marching in the street (see below image, click to expand; public domain) (vol. XIV, p. 236).

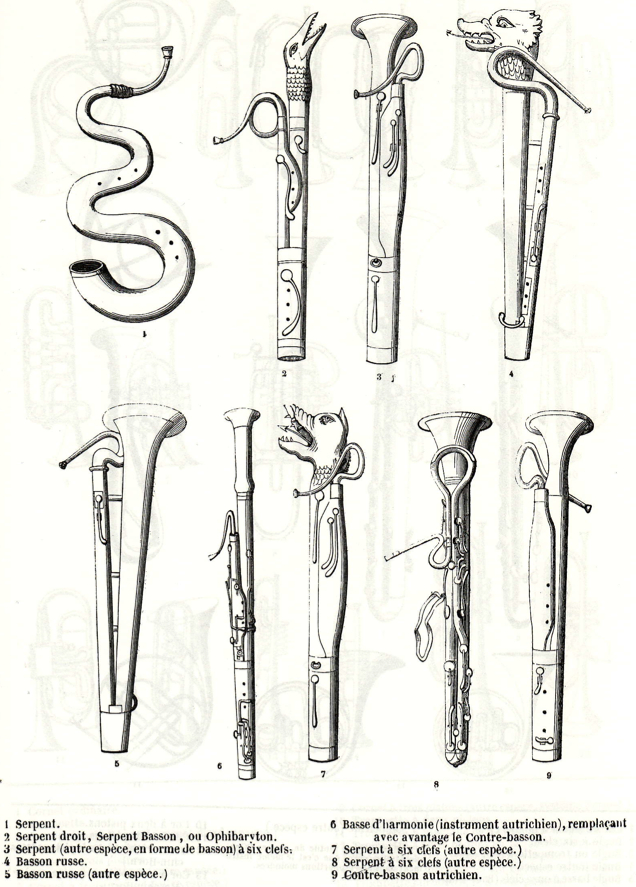

1848—Paris, France: Georges Kastner’s treatise on military music, Manuel Général de Musique Militaire, includes a page illustrating serpents and related instruments (see Kastner’s labels at the bottom of the image) used in military music (see below image; public domain) (Kastner, Militaire Pl. XVIII). 1848—Paris, France: Georges Kastner’s treatise on military music, Manuel Général de Musique Militaire, includes images of a pair of ophicleides used in military music (see below image; public domain) (Kastner, Militaire Pl. XVII).

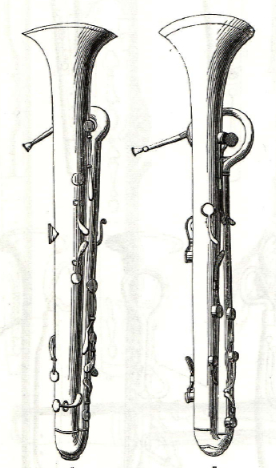

1848—Paris, France: Georges Kastner’s treatise on military music, Manuel Général de Musique Militaire, includes images of a pair of ophicleides used in military music (see below image; public domain) (Kastner, Militaire Pl. XVII).

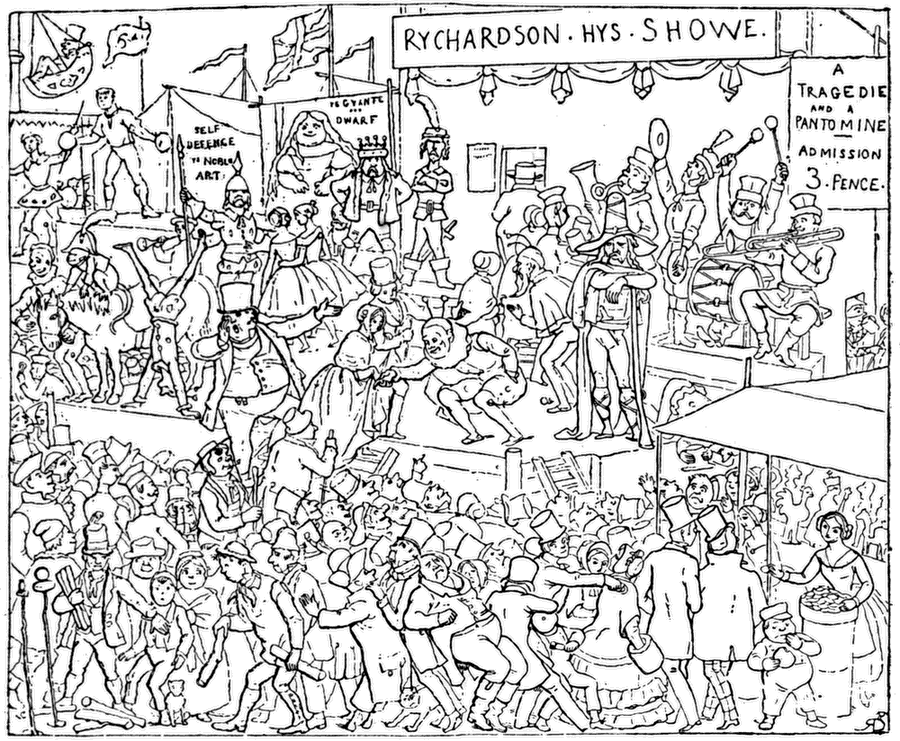

1849—London, England: A drawing in the British weekly magazine, Punch, includes a band with trombone, ophicleide, bass drum, and cymbals. The article attached to the image, titled A Prospect of Greenwich Fair, mentions “half-a-dozen different Bands playing as many Tunes” (May 29, 1849; see below image; public domain).

1849—London, England: A drawing in the British weekly magazine, Punch, accompanying an article titled “Kensyngton Gardens with ye Bande Playinge There,” includes trombone and ophicleide among the band. The article says, “The Tunes played mostly Polkas and Waltzes, though now and then a Piece of Musique of a better sort; but the Musique little more than an Excuse for a Number of People assembling to see and be seen (June 1, 1849; see below image; public domain).

1849—London: England: Ye Brytysh Granadiers a Mountynge Guard at St. James Hys Palace Yarde, one of 40 satirical drawings from Richard Doyle’s Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe in 1849, published in Punch magazine, includes an ophicleide in a marching band (see below image; public domain) (August 1, p. 43).

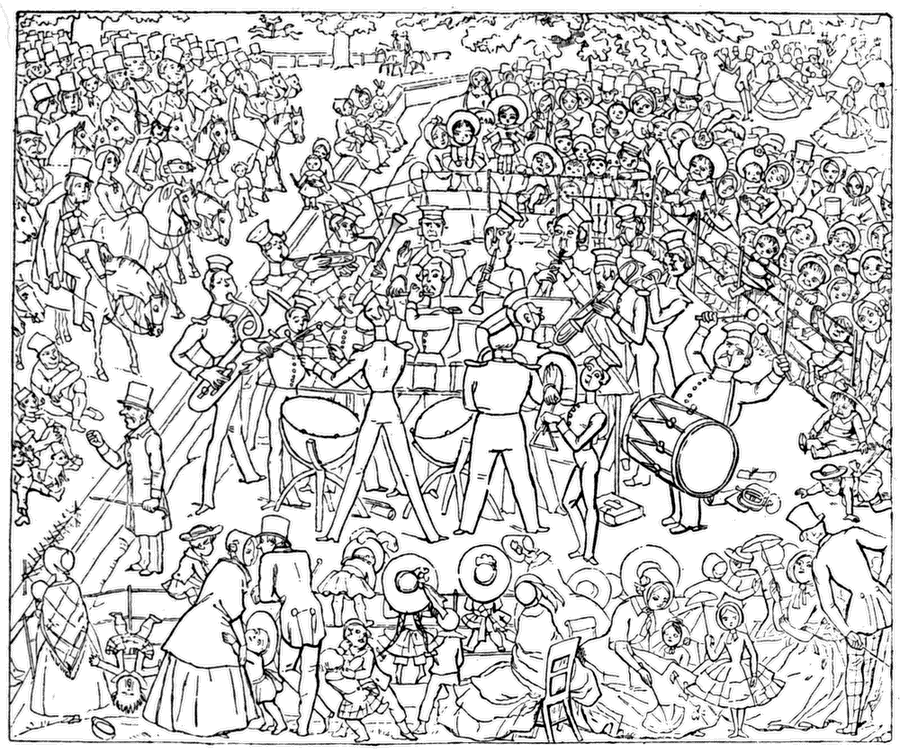

1849—London: England: A Promenade Concerte, one of 40 satirical drawings from Richard Doyle’s Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe in 1849, depicts a large orchestra that includes at least 2 ophicleides (see below image; public domain) (Doyle pl. 40).

c. 1850—Strasbourg, France: Rod Nicker publishes an illustration of an infantry band and sapeurs that includes two ophicleide players (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Ryan 25).

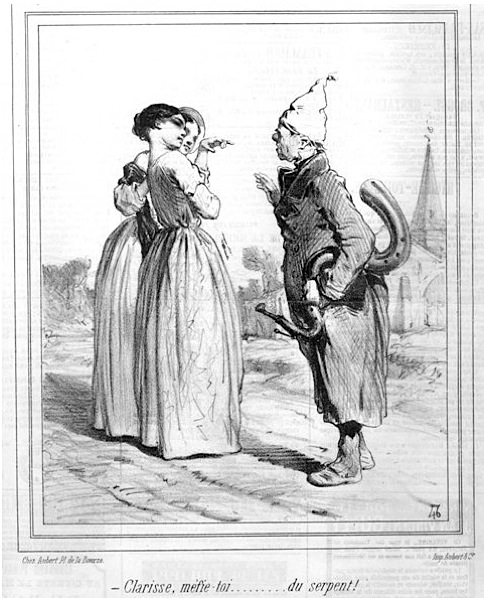

c. 1850—Paris, France: A humorous lithograph by artist Charles Edouard de Beaumont, printed by Aubert, shows a somewhat shabby-looking man with a serpent approaching two women. The caption beneath indicates one of the women saying “Clarisse, beware…the serpent!” (see below image; public domain) (source: Museum of Musical Instruments).

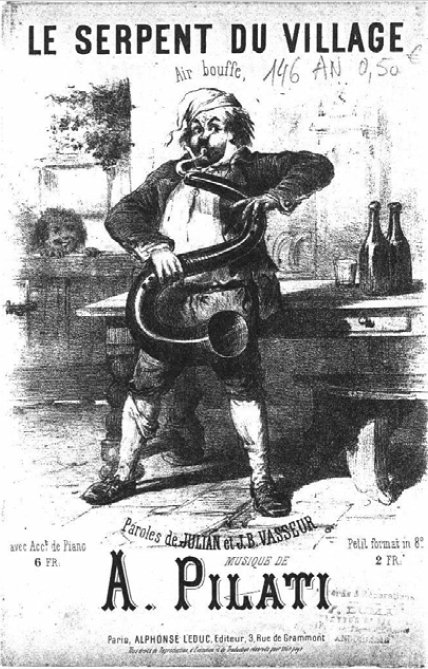

mid-19th century—Paris, France: Alphonse Leduc publishes Le Serpent du Village, a work for serpent or ophicleide and voice by A. Pilati (words by J.B. Vasseur). See below image (public domain). mid-19th century—Brussels, Belgium: A catchpenny print entitled Afbeeldingen van soldaten (Images of Soldiers), produced by Hemeleers-Van Houter, includes a musician playing serpent (see below detail; public domain) (Catchpenny Prints of the Dutch Royal Library).

mid-19th century—Brussels, Belgium: A catchpenny print entitled Afbeeldingen van soldaten (Images of Soldiers), produced by Hemeleers-Van Houter, includes a musician playing serpent (see below detail; public domain) (Catchpenny Prints of the Dutch Royal Library).

1850—An illustration features an ophicleide player from the Coldstream Guards Band in full uniform (see below image; public domain).

1850—Paris, France: The illustrated newspaper L’Illustration publishes a caricature of a religious scene featuring a serpent player accompanying a small group of vocalists (see below image; public domain) (March 30, 1850, p. 205).

1850-1875—France: Musique d’infanterie française, a color lithograph printed by Pellerin, includes 3 ophicleide players among the infantry musicians (see below image–click picture for larger version; public domain) (Paris, Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilization).

1850-1875—France: Musique d’infanterie française, a color lithograph printed by Pellerin, includes a pair of ophicleide players among the infantry musicians (see below detail, click picture for larger version; public domain) (Paris, Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilization).