Yesterday I received a lengthy comment on one of my blog entries about the alto trombone. You can see the original post and comment here. Because of the length of my reply and the number of links I wanted to incorporate, it was easier to post my reply here. I’ve had similar questions/comments from a few other people, so the reply may be of interest to a broader set of readers anyway.

Yesterday I received a lengthy comment on one of my blog entries about the alto trombone. You can see the original post and comment here. Because of the length of my reply and the number of links I wanted to incorporate, it was easier to post my reply here. I’ve had similar questions/comments from a few other people, so the reply may be of interest to a broader set of readers anyway.

Update (June 2016): Upon closer examination of three sources (Nemetz, Seyfried, and Kastner), I have added considerably to the below items of concern. I have also made clarifications to existing items.

__________

Yes, I have in fact read Howard Weiner’s 2005 article, and I agree with you that his is a minority opinion.

Having read the article thoroughly, checked many of its sources, and visited with other scholars, I find more than a dozen reasons that Weiner’s conclusions are unconvincing. There is a pattern of oversimplifying and inconsistently utilizing sources (see items 2-7, below), faulty logic (see items 1, 8 and 9, below), and failure to account for contravening evidence (see items 10-14, below):

1) It is based on only one solid source (Nemetz). The others that he uses are contradictory or unclear at best (e.g., Frölich); see here. This is what David Hackett Fischer famously calls the “fallacy of the lonely fact.” A careful historian will be extremely cautious about generalizing from a single data point.

2) Weiner oversimplifies and thus misrepresents Nemetz. While stating unequivocally multiple times in the article that Nemetz places all three trombones (alto, tenor, and bass) in the key of B-flat, Weiner never mentions that Nemetz also includes a bass trombone in F (“bass or so-called quartposaune”) in his method book. In fact, Nemetz dedicates two full pages to that non-B-flat instrument, including text, a slide position chart, and practice scales. Weiner’s discussion of the “absence” of the quart trombone in Vienna would have been a particularly relevant place for this contradictory information from Nemetz.

3) Weiner oversimplifies and thus misrepresents Praetorius (see here).

4) Weiner oversimplifies and thus misrepresents Berlioz. Although Weiner includes a partial sentence from Berlioz’s treatise (“it is unfortunate that the alto trombone is currently banned from almost all French orchestras”), he fails to mention that, in the same treatise, Berlioz clearly places the alto trombone in E-flat (“small trombone, or alto trombone in E-flat”). This is important because Weiner uses Berlioz as one of just two sources to prove that the alto trombone was considered a B-flat instrument in Paris (for the other source, see #5, below).

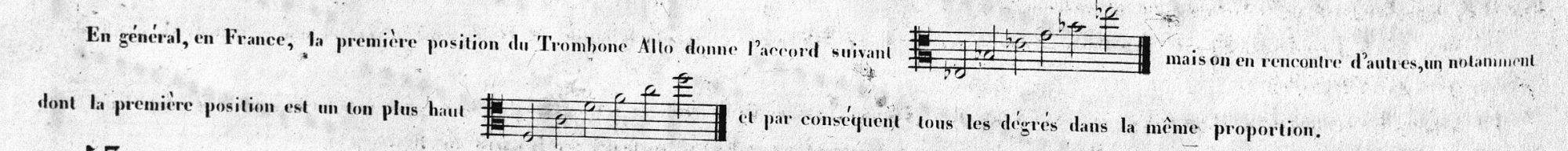

5) Weiner oversimplifies and thus misrepresents Kastner. While paraphrasing Stewart Carter’s paraphrase of Kastner, he overlooks the qualifier “in general” and fails to mention that in the same source (Kastner’s Supplement of 1844), Kastner clearly places the alto trombone in E-flat or F (see the harmonic series in E-flat and the harmonic series in F on p. 40 of the Supplement). And the fact that Kastner likewise places the alto trombone in E-flat in his original treatise of 1837 can only be found buried in a footnote in Weiner’s article (see Kastner’s position chart on p. 313 of the original treatise). This oversimplification is significant because Weiner uses Kastner as one of just two sources to prove that the alto trombone was considered a B-flat instrument in Paris (for the other source, see #4, above).

Kastner’s Traite (1837), p. 313, showing the harmonic series for each position for alto trombone in E-flat

6) Weiner misconstrues Albrechtsberger’s treatise by applying false tones inconsistently. Whereas Weiner is at pains to allow for false or “falset” tones in his discussion of bass trombone—his statement that “I contend that the Viennese trombonists were versed in the use of falset tones” is accompanied by three pages on the practice—the idea is apparently off the table when it comes to alto trombone. Anyone with any kind of playing experience on alto trombone knows that false tones are particularly easy in the low register, the register in question, not to mention the fact that the note would only need to be bent down a single half step. It is unclear why Viennese trombonists would have been well versed in false tone technique on the bass trombone but not on the alto trombone.

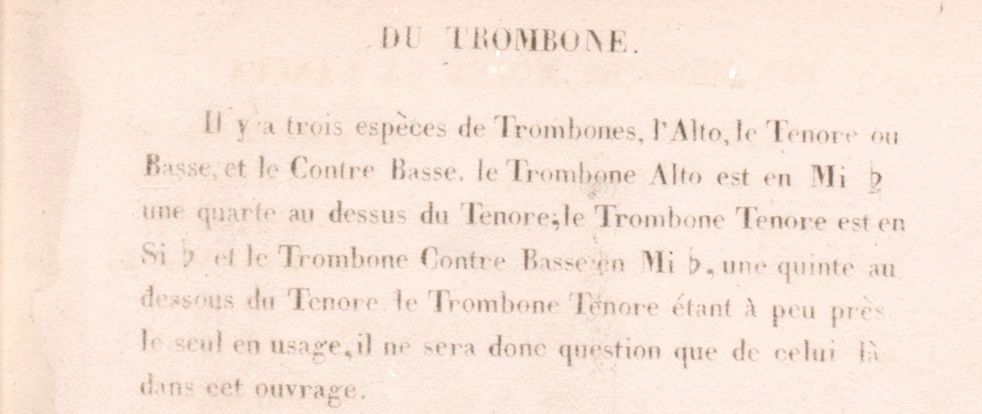

7) Weiner inconsistently uses Seyfried’s edition of the Albrechtsberger treatise to buttress his own argument that the bass trombone is pitched in B-flat, while conveniently discounting Seyfried’s clarification that the alto trombone is pitched in E-flat. If Seyfried is credible on bass trombone, it is not clear why he should not be trusted on alto trombone. This kind of special pleading and inconsistent use of sources is a problem throughout Weiner’s article.

8) Weiner argues from his own personal aesthetic opinion as a premise in the article:

“It therefore follows that a tenor trombone in B-flat or A would have been the virtuoso’s preferred instrument because of its superior tonal qualities. (While there are surely trombonists today who make a nice sound on the E-flat alto, I would contend that they, too, make an even nicer sound on the B-flat tenor.)”

Superior tonal qualities? Even nicer sound? This is neither sound reasoning nor good history (see here). Historians will have their own aesthetic opinions, of course, but when they use their opinion as the premise of an argument, they run aground.

9) Weiner makes a faulty historical generalization from the opinion of one (Praetorius) to many (“any self-respecting eighteenth-century virtuoso”). As I point out above (#3), the generalization from Praetorius is additionally precarious because the partial sentence from Praetorius is already an oversimplification—of the both the sentence itself and of Praetorius’s overall writings about the alto trombone. Again, this is neither sound reasoning nor good history (see here). Furthermore, Weiner’s faulty generalization is stretched chronologically from Praetorius (early 17th century) all the way to any hypothetical virtuoso of the 18th century, a century later! So there are actually three glaring logical problems in just one paragraph: 1) generalizing from one to many, 2) generalizing from an oversimplified statement, and 3) generalizing from one century to another. Here is the full paragraph from Weiner’s article; the non sequiturs absolutely pile up:

“My reasoning for discounting the use of the alto trombone in D or E-flat: It is my belief that any self-respecting eighteenth-century virtuoso would have chosen an instrument that helped him make the most beautiful sound possible. Given the trombone’s physical development, or lack thereof, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, I know of no reason why Praetorius’ judgement, that ‘the sound in such a small corpus is not as good as when the tenor trombone, with good embouchure and practice, is played in this high register,’ should not also apply to the small alto trombone of the eighteenth century. It therefore follows that a tenor trombone in B-flat or A would have been the virtuoso’s preferred instrument because of its superior tonal qualities. (While there are surely trombonists today who make a nice sound on the E-flat alto, I would contend that they, too, make an even nicer sound on the B-flat tenor.)”

10) Weiner misses entirely the Brahms letter in which the highly influential and respected composer notes his preference for the alto trombone and indicates what a “genuine” alto trombone was considered to be at the time: “On no account 3 tenor trombones! One genuine little alto trombone and, if possible, also a genuine bass trombone” (emphasis in original; see here for more details). This information is particularly relevant because Weiner’s claims in the final sentence of the article actually refer specifically to Brahms:

“The newly introduced E-flat alto trombone was most likely not intended to be used for the works of the ‘modern’ composers Brahms, Bruckner, Dvorak, etc., but for the ‘alto’ trombone parts of the classical masters, parts for which the new large-bore tenor trombone was not suitable.”

In addition, although Weiner’s article focuses on the trombone section of the 18th and early 19th centuries in his article, a number of the “historical sources” that he introduces as backing fall well outside of those date ranges (e.g., 1620, c. 1650, 1687). The date of Brahms’s letter (1859) is far closer to Weiner’s date range than any number of the sources presented in the article.

11) If alto=tenor had been true in the widespread way that Weiner suggests, both chronologically and geographically, there should be widespread evidence of that philosophy or viewpoint in contemporary and later treatises, dictionaries, methods, trade catalogs, etc. It is simply not there to the extent that it should be. Of course, absence of evidence does not of itself constitute evidence. However, in this case, the reverse pattern of written sources is observable: the bulk of the written evidence points to a widespread view of the alto trombone as a smaller instrument pitched in a higher key (see here for treatises, dictionaries, and methods; see here for 19th century trade catalogs).

12) Weiner ignores the evidence of existing instruments from the period. A full 25 percent of all existing trombones from before the year 1800 are alto trombones (see here for dates, locations, amounts, and percentages). Even if you adhere strictly to Weiner’s date range of 18th and early 19th centuries (which, as I discuss in #10, above, Weiner himself fails to do), you still have a significant number of alto trombones to account for. The idea that these were primarily amateur instruments lacks documentation: it remains to be shown that amateurs like Moravians used the alto trombone to any greater extent than they used tenor (that is to say, take away the tenor trombones also used by amateurs and you very likely end up with the same overall ratios).

13) Many, many other good historical sources contradict Weiner’s alto=tenor idea, clearly placing the alto trombone in a different, higher key. For example, Weiner uses two sources to prove that the alto trombone was considered a B-flat instrument in Paris; however, not only do those two sources themselves contradict such a conclusion (see #4 and #5, above), but three more primary sources from 1840s France contradict it as well. In fact, the broad historical picture is that, for every historical source that clearly indicates an alto in B-flat, there are at least five contradictory primary sources that clearly indicate an instrument pitched in the E-flat orbit (see here). See also #11, above.

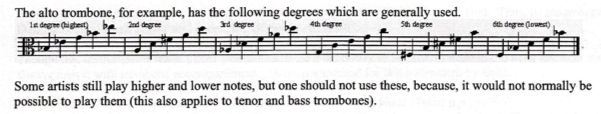

Passage from Hartman’s trombone method, one of 3 additional primary sources from 1840s France that contradict Weiner’s thesis

14) With all due respect, Howard Weiner is not an active trombone performer. I would question whether he has publicly performed any solo work on the alto trombone in the last 20 years (if ever), let alone whether he has played it on both alto and tenor trombone. In addition, I would question whether he has sufficient performance experience on both instruments to determine for other trombone players which is easier (or more “idiomatic”). For example, having the partials of a brass instrument closer together in a given register (as on tenor) can be helpful, at times, but so can having the partials farther apart (as on alto). Ornamentation is one of a brass performer’s concerns, but so is accuracy and security. I was amused to read recently a passage in a trombone history book where another supposed historical “expert” explained to readers that certain works were more idiomatic on tenor trombone than alto trombone; this from a person who had admitted in an online forum that he never actually learned the alto trombone!