Several years ago I posted a collection of captions and images from the Trombone History Timeline reflecting the trombone’s historical use as a dance instrument. I have added to it since then (see 1548, c. 1585, c. 1828, c. 1840, 1873, 1878, and 1948, below). I have also expanded some captions, like the very first entry, which provides more information than recent trombone histories that have been published. Beginning with the trombone’s earliest years as a member of the alta cappella or shawm band, dance music is a consistent aspect of trombone history that is perhaps somewhat underrepresented in the literature.

1459—Florence, Italy: An outdoor ball is hosted by Cosimo de’ Medici on the occasion of an important state visit of the heir to the duchy of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza. A chronicler of the events describes the music and dancing at the ball: “That was the time when the shawms and the trombone [tronbone] began to play a saltarello artistically designed in all its proportions. Then each noble and nimble squire took a married lady or a young girl and began to dance, first one, then the other. Some promenade around, hop, or exchange hands, some take leave from a lady while others invite one, some make up a beautiful dance in two or three parts” (Nevile, Eloquent 150; Nevile, Measure; Sparti 135; Gombosi, About Dance). Earlier in the narrative, the chronicler notes the place reserved for the shawm and trombone players: “Opposite the seigniorial coat of arms above the fence, a place was prepared high up for the shawm and trombone players [pifferi & tronbone]” (Nevile, Eloquent 144). He then records the actual arrival of the shawm and trombone players, including, in this case, a noteworthy description of the trombone: “It was at this time that I saw the shawm players arrive with the trombone [tronbone di tromba torta, or trombone with bent pipe] and go up to their appointed place” (Nevile, Eloquent 146).

1460s—Augsburg, Germany: The city is temporarily without a trombonist for their civic wind band, but continues to hire a trombonist “for especially important dances” (Polk, German 118).

1518—The betrothal of Princess Mary, daughter of Henry VIII, to François, eldest son of François I, King of France, takes place in Greenwich, with a repeat performance in Paris. Festivities include a dance performed by a wind band that probably consists of 3 shawms and 2 trombones (“two brass which were bent back”) (Shaw).

1520—France: King Henry VIII of England meets with King Francis I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. An one point in related celebrations at nearby Guines (France), King Francis leads a dance accompanied by his own fifes and trombones (Russell 164).

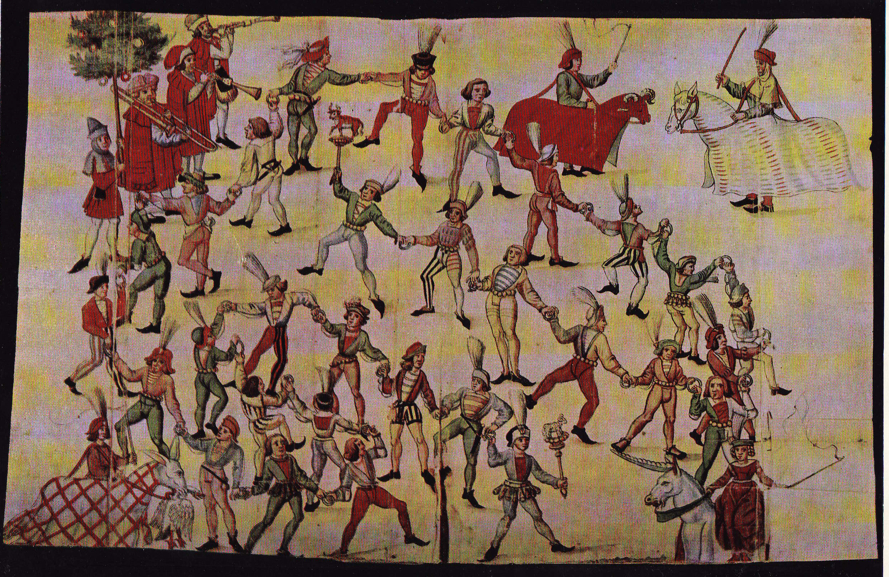

c. 1545—Nuremberg, Germany: An anonymous depiction of a dance, Fastnachtstanz von Metzgern im Jahre 1519 (Carnival Dance of the Butchers in the Year 1519), portrays a trombone as a member of a wind instrument trio providing music for a Nuremberg carnival dance (see upper-right of below image; click on image for larger version; public domain) (Salmen, Musikleben im 16 78-79).

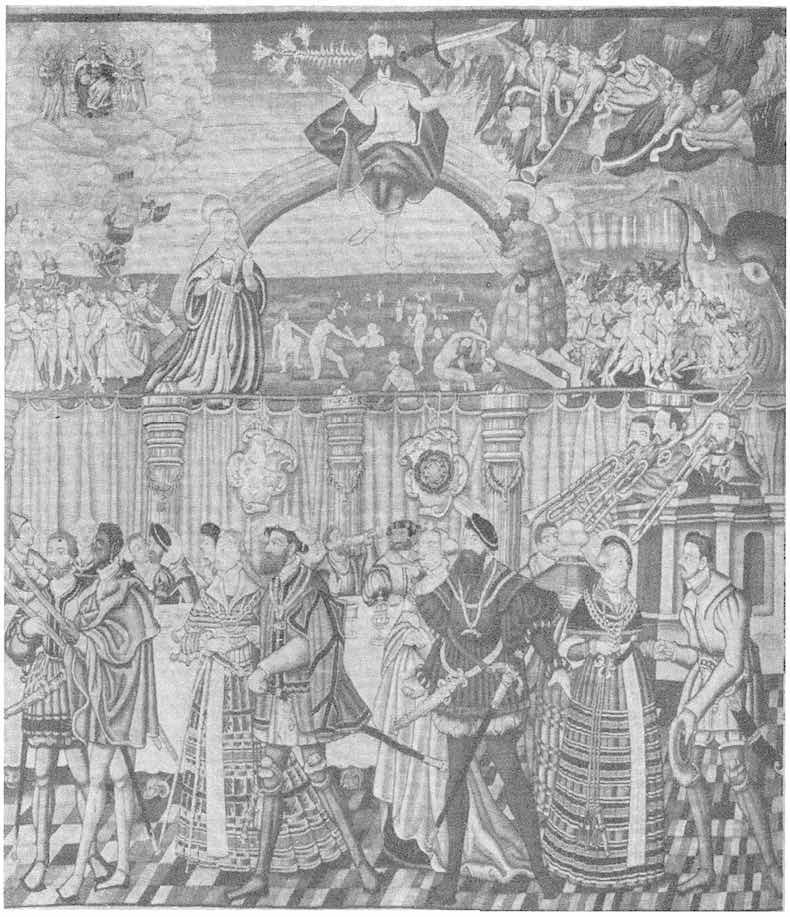

1548—Germany: A tapestry depicting a wedding dance features an ensemble of 2 trumpets and a trombone playing from a balcony (see below image; public domain) (Schlossmuseum, Berlin [now lost]; Führer lurch das Schlossmuseum, pl. 30).

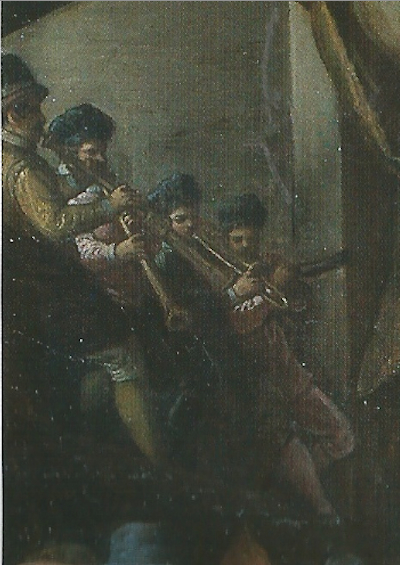

c. 1585—A painting attributed to Paolo Fiammingo (Pauwels Franck) features what appears to be a trombone among a group of 4 wind musicians playing from a balcony or loft (see detail and full image below; public domain).

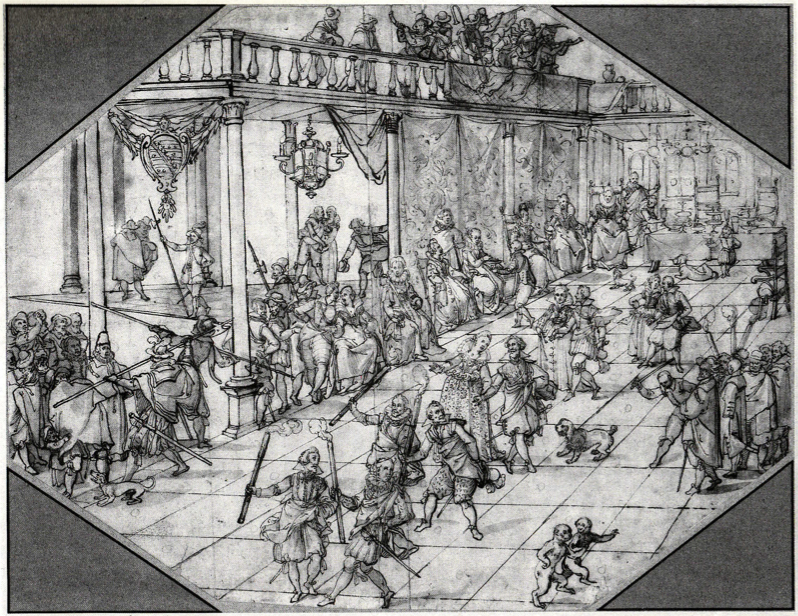

c. 1550—Nuremberg, Germany: Patriziertanz im Grossen Nürnberger Rathaussaal, an anonymous image depicting a dance in Nuremberg’s town hall, includes 2 trombonists among the 5 wind musicians providing the dance music from the balcony. One of the unusual aspects of the image is that both trombonists have banners hanging from their slides (see upper-left of below image; click on image for larger version; public domain) (Nuremberg, Stadtavchiv; Salmen, Tanz im 17 148).

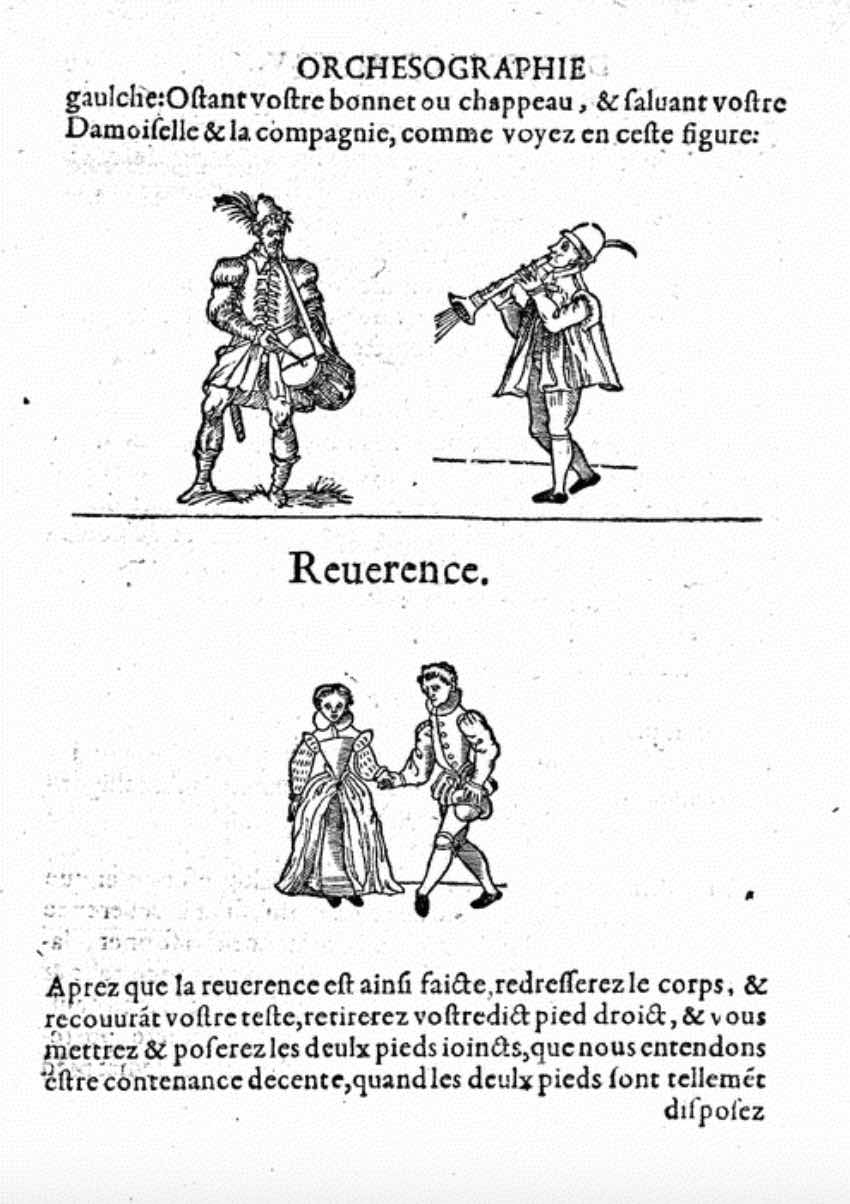

1588—France: Thoinot Arbeau mentions the trombone in Orchesographie, his treatise on dancing. First, he complains, “Nowadays there is no workman so humble that he does not wish to have hautboys and sackbuts at his wedding” (Arbeau 51). Later, he describes use of the instrument by royalty for dances on solemn feast days: “On solemn feast days the pavan is employed by kings, princes and great noblemen to display themselves in their fine mantles and ceremonial robes. They are accompanied by queens, princesses and great ladies, the long trains of their dresses loosened and sweeping behind them, sometimes borne by damsels. And it is the said pavans, played by hautboys and sackbuts, that announce the grand ball and are arranged to last until the dancers have circled the hall two or three times, unless they prefer to dance it by advancing and retreating. Pavans are also used in masquerades to herald the entrance of the gods and goddesses in their triumphal chariots or emperors and kings in full majesty” (Arbeau 59). A page from the treatise is shown below:

c. 1591—Augsburg, Germany: An oil painting by Abraham Schelhas titled Augsburger Geschlechtertanz depicts an aristocratic dance in Augsburg. The 4 wind musicians providing the music play from a balcony and include a trombonist; the other instruments appear to be shawms (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Augsburg, Städtische Kunstsammlung; Salmen, Tanz im 17 151).

c. 1600—Fackeltanz bei Fürstenhochzeit, an anonymous image, possibly from Germany, depicts a torch dance at a prince’s wedding. Instrumentalists supplying the dance music from a balcony include a tombonist (see upper portion of below image; public domain) (Salmen, Tanz im 17 153).

1609—Prince Francesco, setting up his court as governor of the Mantuan province of Monferrato, seeks assistance of Ercole Gonzaga in hiring group of pifferi from Cremona (Kurtzman, Trombe). Claudio Monteverdi is also engaged in assisting Prince Francesco, and refers to the players he is recruiting in a letter to the court secretary. In his description of their abilities he mentions, “They play together well and readily both dance and chamber music, since they practise every day” (Stevens Letters 64).

1616—Stuttgart, Germany: In a separate account of festivities celebrating the baptism of Prince Friedrich von Württemberg (as distinct from the “Assum Version” cited above), the author of the “Weckherlin Version” renders the account into English himself, taking note of the banquet: “None may doubte of the plentie of costlie meate and any kind of daintinesse, and rich shew’s of fountaines, images, beasts and other prettinesse set upon the boord, dressed most artificially, no lesse as of sweet musicke. For there were heard three severall companes th’ one after the’ other, so that when the first (that did sound, after the Italian fashion, instruments and voices together) did finish, the second (playing according to the English manner with cornets and sack-botts) did beginne…” The author then describes a “Ballet of Nations” that follows, in which characters representing various nations crawl out of 4 large heads. Of the trombone’s role he says, “The third that came forthe of the second head was a Laponian, covered with the skinne of a beare, and trampling about at the sound, such an other fellow of Lappie did tune with a sackbotte” (see below image; public domain) (Bowles 209-11).

1700s—The Netherlands: An anonymous eighteenth-century Dutch etching features trombone and cornetto, seemingly dancing as they perform. The text reads, “I have to bend down, holding my instrument of pipes, so as to direct it so it will give a sound. Look how my club hangs from my body, as a result of my movements. Hear my bells ring. I blow the zink and make it sound distinguished. With it I can easily cure the sick. Though I can lower and raise the sound, my lungs remain full of air, and my pochet remains empty” (see below image; public domain) (Naylor 63).

1803—Leipzig, Germany: A writer for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung says, “[The trombone] has spread all over Germany since the days of the French occupation, via the French military bands and the modern German military bands, which are modeled after them, so that, for example, in the vicinity of Leipzig almost no dance can be played without a bass trombone cavorting about” (Lewis, Gewandhaus).

c. 1820—France: An etching titled The French Garrison, probably set in Normandy, depicts a group of French soldiers mingling with villagers. A fiddler and a regiment trombonist with a rear-facing instrument provide music for dancing while standing on a makeshift stage (see upper-right of below image; public domain) (Fromrich 24).

1820s—Stockholm, Sweden: Bernhard Crusell writes 10 military marches and dances for a brass ensemble consisting of keyed bugle, 3 horns, 2 natural trumpets, and trombone. This instrumentation, known as the Hornseptett, soon becomes standard in Swedish military music (Wallace, Brass Solo 241).

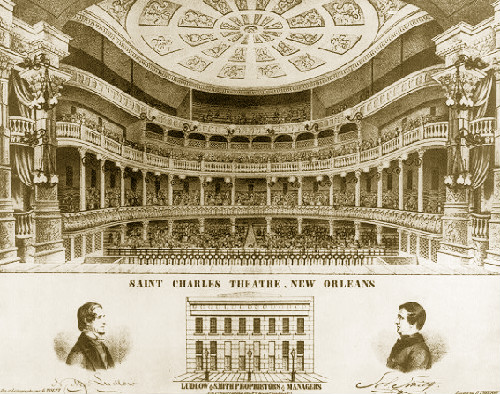

1835—New Orleans, Louisiana: At the St. Charles Theater, when a popular French ballerina dances a new ballet, “The Revolt of the Harem,” she is accompanied by Felippe Cioffi “in a grand trombone solo by Weber” (Kmen 140, 211). A newspaper advertisement for a “grand ballet dance” at the St. Charles Theatre mentions a trombone solo by Felippe Cioffi: “In this beautiful dance Signior Cioffi will accompany Madamoiselle Celeste in a grand Trombone Solo. The whole of the music by Carl Maria von Weber” (New Orleans Commercial Bulletin).

1843—Russia: A lithograph by Rudolf Joukowsky titled Kosakentanz depicts a lively “Cossack Dance.” The orchestra providing the music includes what appears to be a trombone with a slide extension handle (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Berlin, Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte; Salmen, Tanz im 19 75).

Mid-1800s—A trombonist with decorative ribbons on his slide helps provide music for a maypole dance in an anonymous print from the mid 19th century (see below image; public domain).

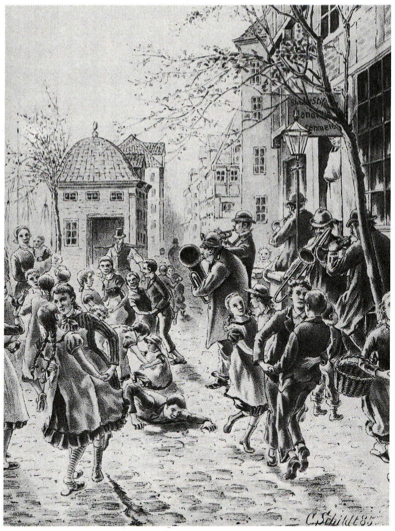

c. 1850—Austria: Artist Carl Schild depicts a group of youth in a street dance in his lithograph, Pannkooken-Musikanten. The brass quintet providing the music includes a trombone (see below image; public domain) (Salmen, Tanz im 19 56).

1853—Paris, France: The illustrated newspaper L’Illustration publishes a graphic, “La danse aux camps,” depicting a military celebration with a four-man dance band in the upper-left that includes what appears to be a rear-facing trombone (see below image; public domain) (L’Illustration, vol. 22, July 23, 1853, p. 64).

c. 1860—Peru: Artist Pancho Fierro depicts a trombonist performing with a wind band for a Peruvian wedding celebration in Fiesta de Matrimonio (see detail and full image below; public domain) (Lavalle 38).

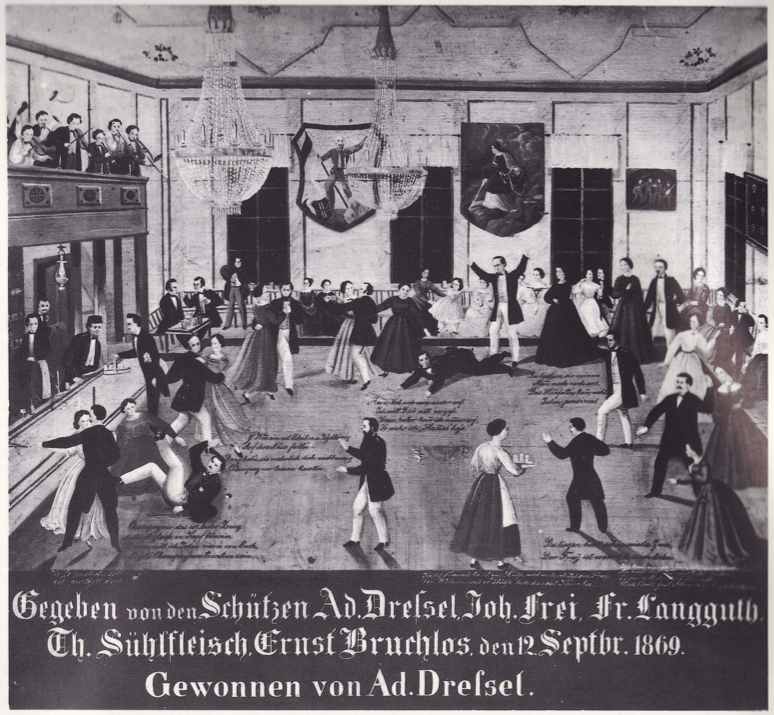

1869—Germany: An anonymous depiction of a ball includes 7 musicians, probably Stadtpfeifer, performing dance music from a loft (see below image; public domain) (Eisfeld, Museum Otto Ludwig; Salmen, Tanz im 19, 129).

1873—France: L’Alsace d’autrefois, an engraving from Le Monde Illustré, depicts a trio of musicians, including trombone, playing for a dance in old Alsace, France.

1873—Paris, France: Christmas Eve in a Spanish Church, a print after Miranda appearing in the Paris illustrated newpaper, L’Illustration, features a buccin, or trombone with a bell in the shape of a dragon’s head (see below image; public domain) (L’Illustration, January 4, 1873, pp. 10-11).

c. 1878—Benjamin Vautier’s painting, Dancing Break at an Alsatian Wedding, features a small group of musicians, including a trombonist apparently emptying the water out of his horn (see below image; public domain). Click image to expand.

1883—Pitanguy, Brazil: Englishman Hastings Charles Dent visits church near town of Pitanguy in Minas Gerais, Brazil, and is entertained with music that includes “guitar, trombone and concertina.” He asks the priest “why they had no sacred music, only dance music in church; he said the people were not educated up to it yet, but he hoped in time to introduce it.”

1948—Maurice Gardner, in The Orchestrator’s Handbook, says, “The trombone is an instrument of many uses. In the symphony and band, its bold, powerful and at times majestic tone is of great value. In radio and the dance band (in the hands of competent performers), the trombone’s lyrical ‘cello-like quality comes to the fore. Today, its ability to play glissando between tones has become a commonplace resource” (Gardner 43).