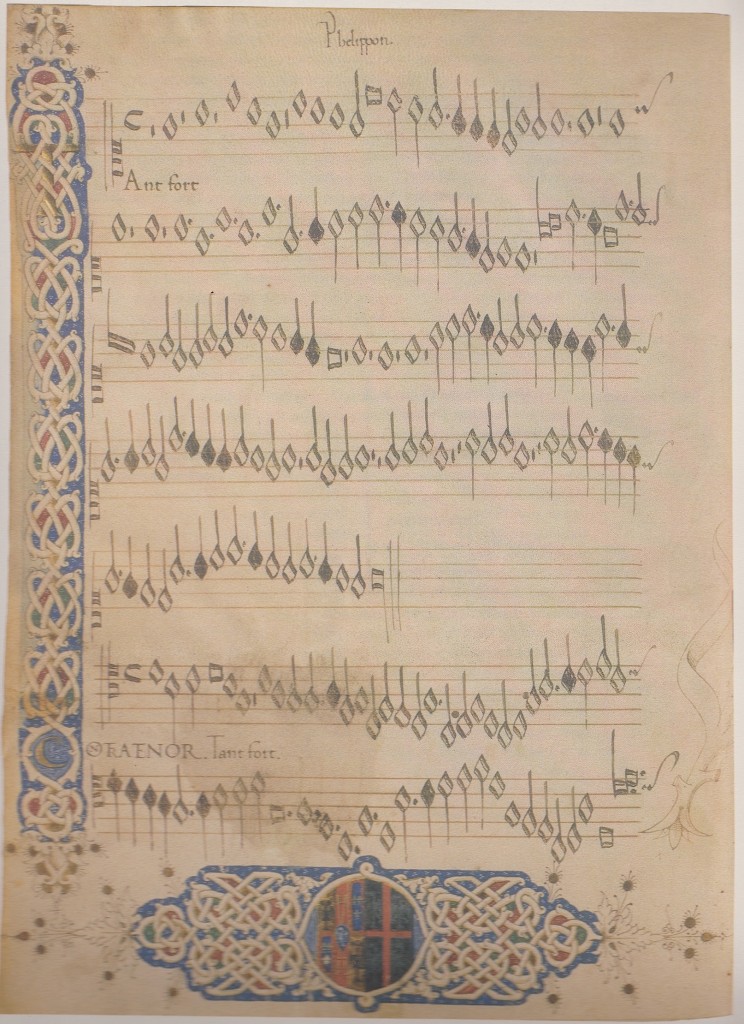

I have now added the below caption about the Casanatense manuscript (also known as the Casanatense Chansonnier or simply Casanatense 2856), to the Trombone History Timeline (15th century).

What is the significance of this manuscript in the history of the trombone? People sometimes claim that there is no written music for the trombone from the Renaissance era. The Casanatense manuscript is a collection of written music dating from the late Renaissance that was likely intended for an ensemble of shawms and trombones. The manuscript doesn’t name trombone specifically (nor does it name any other instrument, for that matter—it would be unusual if it did); however, based on a range of historical evidence, it is likely that this music was intended for an Italian wind band that included trombone. Stewart Carter says, “Casanatense 2856, then, possibly is the earliest surviving source prepared with the intention of including the trombone in the performance of the music, albeit in combination with other instruments” (Carter, Renaissance 40).

Lewis Lockwood, a leading music scholar whose expertise includes the Italian Renaissance, is one of the best sources for information about this collection (see his award-winning Music in Renaissance Ferrara). Another important source is Keith Polk, who has written about the manuscript in several places, including his excellent book, German Instrumental Music of the Late Middle Ages. For a contrasting opinion on the manuscript, see Joshua Rifkin, “Munich, Milan, and a Marian Motet…,” Journal of the American Musicological Society (2003). And for Lockwood’s response to Rifkin’s assertions, see Lockwood, ed., A Ferrarese Chansonnier, xxxi.

THE TIMELINE CAPTION

c. 1480—Ferrara, Italy: The Casanatense manuscript, a collection of secular polyphony “identified with the repertories used by the wind bands of Italian courts and cities” is likely prepared specifically for the Ferrara court’s wind players, including trombones (quote from Brown and Polk, Instrumental Music 128; see also Lockwood, Music in Renaissance Ferrara 299; and Polk, Patronage and Innovation). As Keith Polk says, “In any case, at the very minimum, the repertory contained in the Casanatense manuscript would have been played by the court shawms and trombones, and would have formed a part of the repertory of wind players in general” (Polk, Patronage and Innovation; see also Lockwood, Music in Renaissance Ferrara 299).